In November 2024 the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) named recent Bethel graduate Annessa Ihde a finalist for its Woman of the Year honor. “It’s an award that celebrates not just the athletic portion of being a student-athlete,” she told a local TV reporter, “but also the academic and the community involvement, like how much you were contributing to your campus and what you were doing to serve your community.”1 An All-American in the 800-meter race who helped lead the Royals to their first outdoor conference championship in women’s track and field, Ihde majored in Spanish and international relations at Bethel and worked for local refugee resettlement organizations before and after graduation. She followed in the footsteps of fellow runner Annika Halverson, a 2018 finalist for the NCAA Woman of the Year honor who also won Bethel awards in servant leadership and reconciliation.

Looking back on her career as a six-time All-American in track and cross-country, 2010 graduate Marie (Borner) Ferda celebrated how sports let Bethel student-athletes “use [their] talent to honor and glorify God,” whether they’re women or men. Still, she particularly appreciated that “athletics give women a competitive outlet and encourages you to get uncomfortable and challenge gender and social norms.” The careers of runners like Ferda, Halverson, and Ihde illustrate how sports empower “women to have the same opportunities as men and find similar success with hard work, intensity, commitment, and perseverance — traits that often can be more associated with male athletes than female athletes.”2

But while the present-day women’s track and field team is understandably held up as a model of Bethel’s commitment to whole person education even beyond the classroom, that program didn’t even debut until 1975 — a year when the four teams of “Lady Royals” collectively received one-twentieth of the Athletics Department budget. Basketball had been Bethel’s sole intercollegiate women’s sport until 1967, and only then under a set of rules meant to keep female athletes from doing “unwomanly things.” It wasn’t until years after the 1972 passage of Title IX that Bethel women’s teams began to close gaps in funding, facilities, and other resources and achieve the successes that the university now trumpets.

Micayla (Moore) Franklin ’16, who played softball at a time when “women were excelling in various sports at Bethel,” recalled chatting with alumnae from the 1980s, the decade when Bethel temporarily shuttered its softball program: “When they’ve told me what they had to do just to play the game, I am struck. I realize that we truly do stand on the shoulders of giants. They did so much with so little in institutional support, I marvel at their determination and success. Women like them came before us at Bethel and paved the way for my generation to be successful and get more resources and support that we deserved. We truly are part of a great cloud of witnesses.”3

“A Very Different Universe”: Early Women’s Sports at Bethel

It’s often said that the goal of Bethel University is to form “whole and holy persons.”4 But the earliest articulation of that holistic philosophy of education comes not from John Alexis Edgren, founder of what became Bethel Seminary5, but from the unnamed student who edited the athletics page in the 1909 edition of The Acorn, the yearbook of Bethel Academy:

We admire the motto of the Y. M. C. A.: Mind, body, and spirit. This motto, if followed up closely, will give us a perfect man as far as man can be perfect. The development of the mind is what we primarely [sic] come to school for, and yet we must not forget that the other two are equally as important, in fact more important. It is unnecessary to mention the importance of spiritual development, for we all that know that a man without a clean soul has but little to live for. These first two essentials, mind and spirit, have received due attention at Bethel Academy, but in order to develope [sic] the mind and spirit, development of the body is absolutely necessary.

Yet, he grumbled, “the facilities for this development of body have been inadequate and neglected” on the Academy’s early campus, in the St. Anthony Park neighborhood of St. Paul. Male students boxed and wrestled in the same classroom where they studied Greek and played hockey on the frozen surface of a nearby pond. The one athletic facility praised in those first yearbooks was also the only one where Bethel’s men and women could develop body as well as mind and spirit: the temporary tennis court (below) where students and teachers played mixed doubles in the spring.6

After merging with the Seminary and moving to a new campus on Snelling Avenue, Bethel Academy constructed a new building in 1916 whose gymnasium hosted compulsory physical education courses for both sexes. “Boys and girls have separate entrances with equal shower facilities,” clarified the Academy catalog, “and use the gymnasium on alternate days.”7 In addition to indoor drills in “marching, wand and Indian club,” female students went outside in the fall and spring for hiking and games of volleyball and kitten ball, a precursor to softball.8 After the Academy gave way to the Junior College during the Great Depression, physical education courses spun off intramural competitions for both women and men — competing separately — in basketball, softball, volleyball, and archery.9 As historian Susan Ware has observed, “American girls found lots of opportunities for vigorous exercise and play” in those years, but “their formative athletic experiences occurred as part of their schooling, especially in physical education classes and intramural sports. Here they could not avoid confronting the fact that physical activity for girls occurred in a very different universe than similar activity for boys.”10

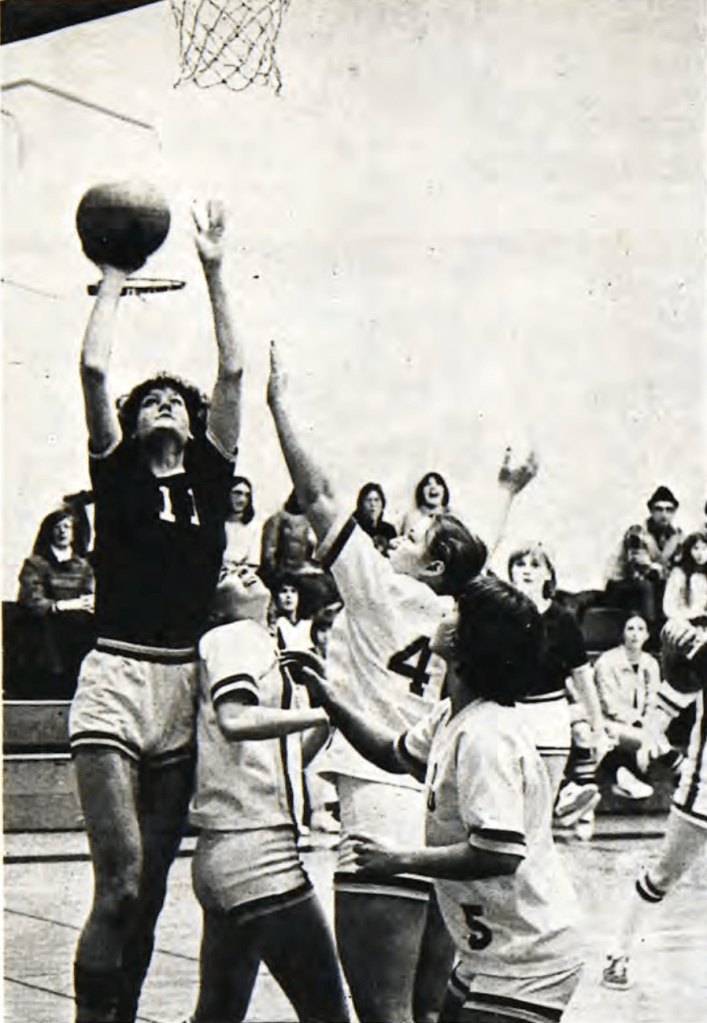

For decades, Bethel’s only intercollegiate sport for women was basketball, which Bethel Academy girls had played in intramural form since 1916, then against other schools as of 1923, when they lost twice to Minnehaha Academy.11 By the 1940s, the Junior College’s “Squaws” — Bethel Royals didn’t supplant Bethel Indians as a nickname until 1952 — played basketball against a variety of teams, from students in the University of Minnesota’s agriculture program to African American women living at the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House.12

But while basketball provided an early competitive outlet for Bethel women, the way that sport was played for most of the twentieth century reflected deep-seated concerns about the femininity of female athletes. Until the 1960s, women’s basketball generally followed Smith Rules, which limited each player to one section of the court, restricted dribbling and defense, and prohibited physical contact. “It is a well known fact that women abandon themselves more readily to an impulse than men,” explained the rules’ primary author, Smith College professor Senda Berenson, in 1903. “[U]nless a game as exciting as basketball is carefully guided by such rules as will eliminate roughness, the great desire to win and the excitement of the game will make our women do sadly unwomanly things.”13 Berenson was a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania, but as sports historian Paul Putz explains, the tension was felt all the more strongly when athletic competition was chiefly valued as an expression of “muscular Christianity”: “For Christian men, participation in sports offered a way to prove their manhood, to establish their credential. For women, sports could be viewed as transgressive, a potential threat to their womanhood.”14

As Bethel College grew into a four-year institution after World War II, male student-athletes could compete against peers from other colleges in baseball, football, tennis, track, and wrestling, as well as basketball. Women had to settle for basketball until the College’s last years on the Snelling Avenue campus, when new physical education professors Carol Morgan and Tricia Brownlee organized teams in field hockey (1967), volleyball (1968), and softball (1969). While the Athletics Department’s periodical in that era didn’t bother to report on any of the women’s teams, the very existence of the “Lady Royals” was still important at a time when approximately ten times as many men as women competed in American college sports.15 As Morgan explained in the 1972 yearbook:

Many girls share this same enjoyment of competition and sports which, in our society, seems characteristic only of men. Unfortunately, however, the majority of girls remain as spectators and for the most part they do so from lack of opportunity to play and to become proficient enough to enjoy a game or sport.

We are seeking at Bethel to provide an opportunity for students to participate in competition with other schools: to learn more about themselves and others through this added dimension of sports: and to find a new and rewarding way to represent Christ.16

“We didn’t have enough players,” remembered Sarah (Reasoner) Zosel ’72, who lettered on all four teams and later entered the Bethel Athletics Hall of Fame. “I remember knocking on doors before we were to leave for a field hockey match trying to recruit some women to play with us. There were no tryouts. Whoever wanted to play, could play.” Competing in sports helped Zosel foster lasting friendships with fellow student-athletes like Kathy Head; they were also among the first women to complete the new physical education major designed by Brownlee and Morgan. While her friend had grown up playing sports in middle and high school, Head appreciated that Bethel provided her first “opportunity to develop and use the physical and leadership gifts God had given me in organized, competitive sports.”17

“The Biggest Discrepancy”: Growing Pains after Title IX

According to Bethel historians G.W. Carlson and Diana Magnuson, “the pressures to add women’s athletics met opposition from those who believed it was unfeminine and those who thought it was not economically viable.”18 But as Bethel College prepared to relocate to Arden Hills in the summer of 1972, women’s sports in the United States received a dramatic boost. That June 23rd, President Richard Nixon signed into law a set of amendments to earlier education legislation, including the thirty-seven words of Title IX: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Three years later, the Ford Administration confirmed that Title IX carried implications for nondiscrimination in college athletics.

“There was a little more pressure on the institution then to give the women things,” said Brownlee, “because Title IX was to create equality between men and women in athletics.”19 But while 1972 is often seen as a watershed moment in women’s sports, we shouldn’t overstate the immediate impact of Title IX on athletics at American colleges and universities. As we’ve seen in the case of Bethel, women’s college sports were already expanding under the leadership of women like Tricia Brownlee and Carol Morgan. With the NCAA officially disinterested in women’s sports, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) organized in 1971 to host its own tournaments, pursuing a distinctive model of college sports in which women were both competitors and decision makers.

In any event, actual parity was years in the making, nationwide and at Bethel. In more than three decades at that college, said Brownlee, “the biggest discrepancy that I saw at Bethel in women and men” had to do with the lingering disparities in athletics in the years following Title IX.20

While she went on to teach psychology for over forty years, Kathy Nevins first came to Bethel College in 1977 to work as a resident director in the Fountain Terrace apartments. Student affairs director Mack Nettleton also hired her to coach women’s basketball, but he ignored Nevins’ offer to chair a Title IX self-assessment committee, as she’d just done at Ottawa College in Kansas. “His view of what was happening at Bethel in terms of women’s athletics,” recalled Nevins, “was, ‘Well, we have so many sports available for men per capita and so many sports for women, and women are not interested. So they have opportunities, they have sufficient opportunities.’ But at the same time, the number of sports available to women and the number of sports available to men were way out of whack.”21 With field hockey disbanding (1974) and the additions of track (1975) and cross-country running (1976), Bethel offered five women’s sports at the time — to nine for men.

As a coach, Nevins soon discovered that men’s and women’s sports still inhabited different universes at Bethel. Scheduling priority went to the men’s teams, and when women did have practice time in the gym, Brownlee occasionally had to kick out male students who mocked their peers from the bleachers.22 While there was a women’s locker room by the time Nevins started coaching, “it was a women’s locker room, not the football locker room or the athletic locker room and then the general locker room. It was just one.” Female student-athletes car-pooled to away games while their male counterparts took a bus, and Nevins had to bring her squad to McDonald’s while “the men’s basketball team were eating at steakhouses.”23 At the end of the Seventies, the Lady Royals still faced another scarcity that Kathy Head remembered well from the start of the decade: “We used the same uniforms for volleyball and basketball and bought our own softball shirts.”

Still, Head credited Tricia Brownlee and Carol Morgan for not shrinking from “many difficult uphill battles to provide a quality athletic program and experience for young women like myself. They had to fight tradition, administrators and men’s coaches who were reluctant to change or to provide finances.”24

Most of those battles happened behind closed doors, but in 1975 Brownlee took the fight over finances into the full view of Clarion readers. “Women’s sports are a vital part of the college curriculum,” she told the student paper that March. “If sports are good for men, then they must be good for women, too.” Yet Bethel spent just 4.3% of its athletics budget on women’s sports, placing the Royals near the bottom of Minnesota’s two dozen AIAW members. “We certainly don’t want to cut the men’s program simply to increase the women’s,” Brownlee reassured readers. “We don’t want equality, just a more realistic approach to the situation.” While insisting that Bethel provided “adequate opportunity for high-level competition in both men’s and women’s sports,” athletics director Gene Glader acknowledged that Bethel was struggling to keep up with the rapid pace of change: “We have viewed in the last five years an evolution of ideas in women’s sports that has taken men 50 years or more to achieve. For example, it was just five years ago that the men’s track team at Bethel acquired official meet uniforms, but this program began in the early 1940s.”25

“The three men in the [Physical Education] department who were coaches were wonderful Christian men,” said Brownlee in a 2024 interview, “but they were used to having everything they wanted. Well, not at Bethel. They didn’t have everything they wanted. Finances were always an issue. But they were used to pretty much controlling the facilities on the budget. Carol [Morgan]… was nicer than I was. She had been a Christian for many years and knew what it was like to work in a Christian institution with limited resources. But it was just a constant battle to get facilities and money for the women.”26 Brownlee moved into Bethel’s administration in 1977, retiring in 2001 as the first woman to serve as dean of academic programs in the College.

“The attitude toward women’s sports until now has been such that many girls who might like to become involved hold back, afraid of sacrificing their femininity for a healthy body. We hope the athletic department will lead the way in dispelling this vision of the past, and place a higher priority on women’s sports — in its budget and its attitudes.”27

Clarion editorial in March 1975

Sex-Segregation vs. Sex-Integration in Sports

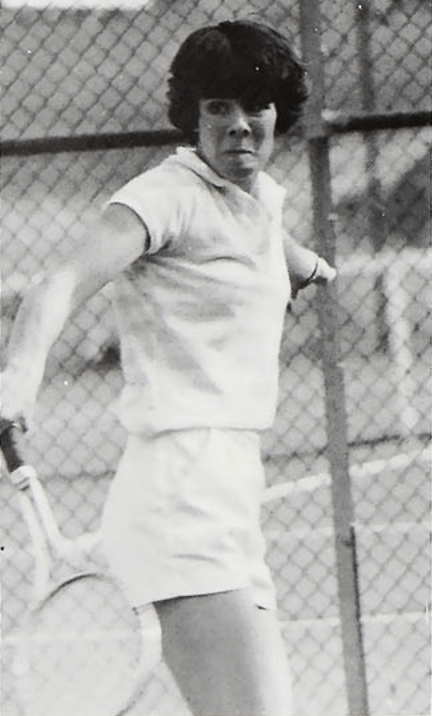

In the spring of 1974, Dana Doolittle and Linda Cumings became the first women to play on Bethel’s tennis team. “Neither girls [sic] claim to bear a women’s liberation banner,” emphasized The Clarion, quoting Doolittle’s explanation that “I just love to play tennis… I wanted to be on a team and they didn’t have a girls team.”28 That wasn’t entirely unusual in that era; one month before Title IX became law, a Minnesota judge ruled that the state’s high school league could not forbid two girls from competing with boys in tennis (or cross-country running and cross-country skiing), since their schools didn’t field girls’ teams in that sport.29 In 1973 a letter to the Clarion editor had shrugged off the fact that a female student from Macalester won her match against a male Bethel athlete in that same sport: “They’re both playing tennis, and in terms of win-loss, who cares about anatomy?”30

Yet the Clarion‘s story on Doolittle and Cumings added that the notion of sex-integrated teams caused “some apprehension” among female and male coaches at Bethel. Athletic director Gene Glader warned that “if men go out for women’s teams, there aren’t going to be too many women who are going to make it.” Meanwhile, Carol Morgan said she and other women coaches were “not interested in running the same type of program as the men do,” echoing the AIAW’s commitment “not to simply ape men’s sports.”31

While Title IX created pressure to expand intercollegiate sports options for women at Bethel and other colleges, it did so by creating what James Druckman and Elizabeth Sharrow describe as “separate but equal” conditions that are “outlawed or outmoded in almost every other social realm.”32 While such critics now blame sex segregation for preserving male domination in sports, women coaches, AIAW leaders, and even many feminist activists in the 1970s supported that approach to gender equality, which provided women with space for autonomy and leadership.33 Here they found unlikely allies among conservative Christians. Historian Paul Putz has suggested that complementarianism — the view that God has ordained distinct roles for men and women under the headship of the former — “existed easily within the world of sports” precisely because “the American sports system was already organized around gender distinctions, with men and women competing on separate teams and in separate leagues.”34

Nevertheless, Bethel was expanding sex-integrated sports options that could complicate assumptions about masculinity and femininity — not intercollegiate competition, but intramural. “Participation in sports activities is a valuable social and recreational experience,” explained the 1972-73 women’s athletics handbook, “and it is our hope that every woman student will take the opportunity to participate in one or both of these programs.”35 Within five years, the intramural sports program not only included women’s acrobatics, badminton, paddleball, softball, table tennis, tennis, and volleyball, but several “coed” activities.36 Rules for those intramural sports aimed to foster both inclusion and fair competition. In coed volleyball, for example, the 1977-78 handbook required that “50% of the players must be girls” and “hits MUST be alternated between men and women.” Similar rules applied to coed basketball, which added the provision that “girls standing on men’s shoulder’s [sic] is permissible (on offense only).”37

Then there’s the mixed-gender intramural sport that “seemed to involve every student in the school” by the start of the Eighties: broomball.38 The Clarion had mentioned Bethel students playing that staple of Minnesota winters as early as 1960 (as a “girls” event during Sno Daze), but a coed broomball tournament only became a January term tradition after the move to Arden Hills, with games initially held on the frozen surface of Lake Valentine.39 Reporting on the 1979 championship, The Clarion highlighted how “the Butcher females constantly frustrated the Family’s high-scoring forwards in their attempts to organize an offensive attack.”40 Five years later, sports editor John Clark described broomball as

the greatest personality changer this side of a prefrontal lobotomy. I don’t mean to sound sexist but I’m amazed at the ferocity of the women on the ice. Guys are basically aggressive players but some of these women put the guys to shame. Are they tough? Yes. Go into the corners with them? No way!41

Coming into Its Own: Women’s Sports since the 1980s

When the Carter Administration began to enforce athletics provisions related to Title IX in 1979, it didn’t mandate equal numbers of teams or athletes, but it did require substantial parity in funding and comparable opportunities “as the interests and abilities of women students developed.”42 However, in a 1984 case involving Grove City College, a conservative Christian school in Pennsylvania, the Supreme Court functionally limited the requirement for athletic parity to the provision of athletic scholarships, raising the specter of decreased funding for women’s sports, particularly at smaller colleges that didn’t offer such scholarships.

The following year Bethel did eliminate one of its women’s teams — not because of the Grove City decision, but thanks to an economic crisis created by a steep decline in enrollment. To help balance its reduced budget, the Athletics Department dropped both women’s softball and men’s wrestling in 1985. “Any time you eliminate a sport, you’re eliminating potential students,” admitted athletic director George Palke. “However, in choosing to drop these sports, we sought to determine how the fewest people would be affected, while still making significant dollar savings.”43

But the mid-Eighties also brought a major boost to women’s sports at Bethel with the 1986 hire of Deb Hunter as women’s basketball coach. The daughter of a Bethel-educated Baptist pastor, Hunter had been an All-American guard for the University of Minnesota, leading the Gophers to the last two AIAW tournaments before the NCAA launched its own women’s tourney in 1982. In her ten years as Lady Royals coach, Hunter won nearly 65% of her games, bringing home Bethel’s first MIAC championship in 1994 and winning a spot in the NCAA Division III Final Four in 1996. “Some women’s teams didn’t get as much attention as our basketball team,” remembered Vicki (Estrellado) Seim, but during those championship runs “the entire community was always cheering for us. It was an amazing experience because it seemed that everyone was involved.” A sharpshooting guard on the 1994 and 1996 teams, Seim credited Deb Hunter for having “pushed for excellence on and off the court.”44 As coach and women’s athletic director, Hunter also advocated for women’s sports in ways that were new to Bethel. “When she came,” said Kathy Nevins, “she kept pulling out the paperwork and saying, ‘We’re not in [Title IX] compliance, we’re not in compliance, we’re not in compliance.'”45 In 1990 Hunter was named one of the Division III representatives on the NCAA Committee on Women’s Athletics, telling The Clarion that such work reflected “a commitment to what I believe is important—making sure there are reasonable opportunities for women.”46

A large bipartisan majority in Congress had restored larger Title IX coverage to women’s athletics in 1988, overriding the veto of President Ronald Reagan. By 1994 colleges and universities receiving federal financial aid were required to file annual Equity in Athletics disclosures. In 1995-96, Deb Hunter’s last year at Bethel, the school reported 140 women playing seven NCAA sports, accounting for about 35% of the student-athletes on campus. “Bethel College is committed to gender equity and has been making steady progress in this area,” wrote student life vice president Judy Moseman, “as demonstrated by increases in coaching and administrative loads for women’s programs, the addition of two programs for women” — soccer’s launch in 1993 and softball’s revival in 1994 — “and increases in the budgets for women’s sports,” plus “a modest reserve fund in the operating budget to address any gender inequities which may arise.”47

The additions of ice hockey (2001) and golf (2009) brought the list of women’s sports level with that for men, and the women’s share of the Athletics budget is now more than eight times what it was in Brownlee’s and Morgan’s time. The size and cost of the football program help account for some lingering disparities. However, Bethel’s most recent Equity in Athletics report points out that if football and the two basketball teams are removed from the calculation, the remaining women’s teams actually account for slightly more spending than those for men.48

| Bethel Equity in Athletics Report, 1995-1996 | Bethel Equity in Athletics Report, 2023-2024 | |

| Women as % of varsity student-athletes | 35% | 37% |

| Women’s share of overall athletics expenses | 24% | 42% |

| Women’s share of recruiting budget | 12% | 26% |

| Average salary of women’s team head coaches as % of men’s | 58% | 83% |

But while women now make up 44% of all NCAA student-athletes, they account for only 25% of head coaches. Women head up only 6% of men’s teams across the NCAA (and none at Bethel49), and it’s also become much less likely over time for women to coach women. In 1973 92% of women’s college teams had female head coaches; fifty years later, that figure is down fifty points.50 The number is even lower at Bethel, where Penny Foore (softball) and Gretchen Hunt (volleyball) are currently the only women to head women’s teams.

Hunt first came to Bethel as an assistant coach in 1998, while finishing her master’s degree at the University of Minnesota, then took over as head coach in 2001. At first, she joined a “split department,” where it felt “a little adversarial to be like a men’s program and a women’s program… They actually didn’t always get along very well because coaches had different goals and felt like, you know, maybe with scarce resources, they were being pitted against each other.”51 But she values how the programs have merged into a single department in the early 21st century:

When you get outside of Bethel in Athletics… you go to women’s coaches symposiums, which I do, and clinics, it can get very, like, “us against them” and very militant: “We should be asking for this and demanding this and doing more.” When I’m part of the team [at Bethel], what I’m always thinking about is just, “How do we move this whole team forward? And how do we do that without leaving? Yeah, I don’t want to leave anybody behind, but also I don’t want this to come at the expense of something great [that] someone else has going on.”

Both the head coach of a team that’s often in the Division III Top 25 and Bethel’s associate athletic director for NCAA compliance, Hunt concluded, “We have such strong outcomes on the women’s side that for me that [it] gets hard to say, ‘Well, something’s going wrong.'”52

While Foore put Hunt atop her list of women role models at Bethel in her 2024 oral history interview, she acknowledged that “Gretchen and I have a lot of the same values but very different personalities and very different ways that we approach things.” Though she has led Royals softball to its first conference championships and NCAA tournament appearances, Foore did admit that the nine-year interruption in her program’s history meant that “it still feels like we’re running up against obstacles,” from having to share facilities to lingering impacts on “building relationships and donors… I’ve been pushing really hard, and I thought I would be a little further along in ten years, but not yet.”53

Her players have noticed Foore’s efforts and learned from them. “Penny advocated for our program to get the resources we were entitled to under Title IX,” recalled Micayla Franklin. “We got more coaches and funding as a result, which helped us immensely. Not only in material support, but also in the more internal, mental support. As in, ‘Yes, you matter, we take you seriously as a student athlete and you are entitled to resources, too.'”54 Current softball player Mandi Franks, a biochemistry major, credits Foore with teaching “all of us not to be afraid to take up space and that we deserve to be heard. Of course, this is helpful on the field, but more so in other areas in my life. In labs and small groups I am inspired to continue voicing my opinion even after being ignored the first, second, or even third time.”55

Franks still sees “a gap between being a female and male athlete here at Bethel,” in terms of resources and recognition, but her coach appreciated the “support that we’ve gotten from fans,” whether those who have streamed NCAA tournament games online or Bethel president and first lady “Ross and Annie [Allen] showing up to the games” in person. And whether it means winning conference championships or persevering through defeats, Foore finds sport especially important because it “helps women find their voice. I think it helps redefine beauty a little bit in the ways that we see beauty. That there’s something beautiful about being strong and powerful, and you can still be feminine while you do that. And then just figuring out that we’re all created for different purposes and in different ways, and you can have really, really different people working for the same goal, which at the end of the day, that’s the Kingdom of God, too.”56

Introduction | Debating Gender | Women in Ministry | Policies and Persons

Women and Sports | Conclusion

NOTES

- CBS Minnesota, November 25, 2024. ↩︎

- Marie Ferda, email interview with author, October 8, 2024. Note that all email and oral history interviews from 2024-25 are quoted by permission of the interviewees. ↩︎

- Micayla Franklin, email interview with author, January 10, 2025. ↩︎

- See Stanley D. Anderson, Becoming Whole and Holy Persons: A View of Christian Liberal Arts Education at Bethel University, rev. ed. (Bethel University, 2018); Christopher Gehrz, ed., The Pietist Vision of Christian Higher Education: Forming Whole and Holy Persons (IVP Academic, 2015); and Jeannine K. Brown, Carla M. Dahl, and Wyndy Corbin Reuschling, Becoming Whole and Holy: An Integrative Conversation about Christian Formation (Baker Academic, 2011). ↩︎

- In his oft-cited set of four educational principles, Edgren did articulate the need for both intellectual and spiritual formation and hinted at the importance of relational growth, but he said nothing about physical development; L.J. Ahlstrom, John Alexis Edgren: A Biography (Conference Press, 1938), 86. ↩︎

- The Acorn, 1908-09, 17; The Acorn, 1909-10, 19-20. ↩︎

- Bethel Academy, 1922-23 Catalog, 12-13. ↩︎

- The Bethannual, 1922-23, 81. ↩︎

- See, for example, The Spire, 1940-41, 42. ↩︎

- Susan Ware, Title IX: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007), 9-10. ↩︎

- The Acorn, 1915-16, 26; The Bethannual, 1922-23, 76. ↩︎

- See, for example, the game reports in The Clarion, March 7, 1940, 4. ↩︎

- Senda Berenson, Basket Ball for Women (American Sports, 1903), 37. ↩︎

- Paul Emory Putz, The Spirit of the Game: Christianity and Big-Time Sports (Oxford University Press, 2024), 165. See also Arthur Remillard, Bodies in Motion: A Religious History of Sports in America (Oxford University Press, 2025), ch. 8. ↩︎

- On the lack of publicity for early Lady Royals teams, see the 1966-1969 issues of Bethel Royal Sports archived in the Eugene Glader Papers, Box 4, The History Center: Archives of Bethel University and Converge (hereafter HC). For numbers of men and women competing in intercollegiate athletics in the Sixties and Seventies, see Ware, Title IX, 9. ↩︎

- The Spire, 1971-72, 23. ↩︎

- Sarah Zosel and Kathy Head, email interviews with the author, November 6, 2024 and November 23, 2024, respectively. ↩︎

- G. William Carlson and Diana L. Magnuson, Persevere, Läsare, Clarion: Celebrating Bethel’s 125th Anniversary (Bethel College and Seminary, 1997), 46-47. ↩︎

- Tricia Brownlee, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, June 24, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Brownlee oral history. ↩︎

- Kathy Nevins, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, June 24, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Brownlee oral history. ↩︎

- Nevins oral history. ↩︎

- Head email interview. ↩︎

- The Clarion, March 14, 1975, 8-9. ↩︎

- Brownlee oral history. ↩︎

- The Clarion, March 14, 1975, 2. ↩︎

- The Clarion, April 26, 1974, 4. ↩︎

- Sheri Brenden, “Gaining Sweat Equity: Girls Push for Place on High School Teams,” Minnesota History 67 (Spring 2020): 7-16. ↩︎

- The Clarion, March 30, 1973, 5. ↩︎

- The Clarion, April 26, 1974, 9; War, Title IX, 11. ↩︎

- James N. Druckman and Elizabeth A. Sharrow, Equality Unfulfilled: How Title IX’s Policy Design Undermines Change to College Sports (Cambridge University Press, 2023), 14. ↩︎

- On this debate within feminism, see Erin E. Buzuvis, “Title IX: Separate but Equal for Girls and Women in Athletics,” in The Oxford Handbook of Feminism and Law in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2021), 388-405. ↩︎

- Putz, The Spirit of the Game, 167. ↩︎

- Bethel College, 1972-1973 Women’s Intramural and Intercollegiate Sports Handbook, in Glader Papers, Box 4, HC. ↩︎

- Bethel College, 1976-77 Intramural Sports Handbook, in Glader Papers, Box 4, HC. ↩︎

- Bethel College, 1977-78 Intramural Sports Handbook, in Glader Papers, Box 4, HC. ↩︎

- The Clarion, February 29, 1980, 8. ↩︎

- See The Clarion, January 14, 1960, 1; and The Clarion, February 3, 1974, 2. ↩︎

- The Clarion, March 9, 1979, 8. ↩︎

- The Clarion, January 20, 1984, 8. ↩︎

- Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, “A Policy Interpretation: Title IX and Intercollegiate Athletics,” December 11, 1979. ↩︎

- The Clarion, February 12, 1988, 1. ↩︎

- Vicki Seim, email interview with author, December 6, 2024. ↩︎

- Nevins oral history. ↩︎

- The Clarion, November 30, 1990, 3. ↩︎

- Bethel College, 1995-96 Equity in Athletics disclosure, in Kathy Nevins Papers, Box 3, HC. ↩︎

- Bethel University, 2023-24 reported data, Equity in Athletics Data Analysis, U.S. Department of Education, accessed August 3, 2025. The women’s share of expenses figure includes half of the $1.4 million reported as not being allocated by sex or sport; if we focus only on expenses explicitly attributed to men’s and women’s teams, the latter accounts for 38% of the $2.6 million total. ↩︎

- Currently, women do coach men as assistants on Bethel’s cross-country and track teams. ↩︎

- Ware, Title IX, 15; NCAA Demographics Database, 2023-24 report, accessed August 5, 2025. ↩︎

- Steph Williams O’Brien, now a pastor in Minneapolis and preaching professor at Bethel Seminary, played on some of the first Bethel women’s hockey teams. “There was conflict between the male and female teams here at Bethel and who got priority of the ice time,” she remembered. “And sometimes that was passive aggressive and sometimes that was direct, but the learning to share was a real big part of that time.” See Steph Williams O’Brien, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, July 16, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Gretchen Hunt, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, July 10, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Penny Foore, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, August 6, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Franklin email interview. ↩︎

- Mandi Franks, email interview with author, December 15, 2024. ↩︎

- Foore oral history. ↩︎