The “ideal girl,” said one speaker, “ought to be attractive” as well as intelligent. Another found beauty less essential than “personal cleanliness and neatness,” while still another said the ideal girl “would have to have an abundance of longsuffering patience… because of the hardships that a girl who would go through life with me would face.” Speaking in the Bethel College dining hall, everyone on the dais agreed that the ideal girl would be a Christian, with one orator insisting that next to “an absolute consuming love for Jesus Christ… all else in life takes second place, even getting married.”1

While each adopted the voice of a young man preparing for courtship, it was women who were describing their “ideal girl” on March 21, 1957: female faculty and staff at Bethel and wives of male professors, invited to address students in the Bethel Women’s Association (BWA) by its founder, Effie Nelson, the German professor who also served as dean of women.

That unusual program offered an unusually clear example of one role that colleges have played in modern American society: setting gender expectations for young adults about to start their own lives, their own work, and their own families. Any women’s history of a place like Bethel needs first to grapple with the ways that gender norms and gender roles were articulated, modeled, and contested on that campus, particularly as the people of that Christian university debated the ideas associated with second-wave feminism.

“Is This All?”: Ideals and Expectations for American Women after World War II

Such themes will show up throughout this project, especially in the essays on women in ministry and women’s sports. But we’ll start by imagining the questions that may have been going through the minds of the young women gathered that spring afternoon in 1957.

What did it mean to be “feminine”?, at least one of them may have wondered, especially after Ingeborg Sjordal warned that “a girl must act like a girl.” Bethel’s Swedish professor had “no sympathy for a girl who pulls on a pair of men’s ‘levi’s’ and a sloppy shirt,” since the ideal girl had to possess “looks and features… that will capture my gaze on every occasion.”2 But was her vision of femininity a universal, timeless ideal, or a set of personal preferences shaped by ever-shifting cultural influences? Indeed, how the women in Bethel’s student body presented Sjordal’s “looks and features” changed as that Baptist college entered the 1960s. “Some of us are concerned about the increasing worldly look of our women students,” Florence Oman (later Johnson) complained privately to Effie Nelson. Then an assistant to President Carl Lundquist, Oman wished “that our Bethel girls could be distinctive and Christian looking without losing their cuteness and charm.”3 Yet some of her particular bugaboos were becoming more common. In a 1963-64 survey of incoming students, 99% of the women respondents approved of cosmetics, while one in three said wearing short skirts was at least sometimes acceptable and only one in five rejected such attire outright.4

In 1957 Carol Anderson thought that the key traits of an ideal girl were not unique to women, since they were “essentially Christian characteristics” that applied equally to men. Nevertheless, she advised BWA members that “simply knowing how to cook or keep house well” would make them “far superior to the many girls whose only accomplishment is ‘knowing how to make themselves attractive.'”5 So was she at college to attract a husband and learn to keep house for him?, one listener surely asked herself. What if she aspired to become a research scientist like Anderson’s husband Elving, a geneticist who had helped to found Bethel’s biology program? After all, that year’s academic catalog promised to introduce the Bethel student “to a wide range of vocational possibilities, including some areas that may be new to him” — and, presumably, to her.6

Female students in that era of Bethel history could choose from a handful of professional pathways, though few of those options would have been “new to” American women of the time. By 1954, five years after Bethel College graduated its first seniors, fourteen of the first 39 women to earn that degree were already married, with the others “quite evenly distributed over the fields of teaching, social work, missions, church secretarial and office positions, and graduate school.”7 When the Bethel Women’s Association held its annual Commencement Tea in 1960, all but two of the graduates listed in the program planned to pursue careers or graduate study, albeit in fields that had long been open to women: education (14), social work or public welfare (5), and religious education (2).8

If those Bethel alumnae didn’t want to marry and perhaps set aside those career plans in order to raise children, Effie Nelson and several other pioneering women professors offered a different model of Christian vocation for modern women: professionalism in the workplace, singleness at home. While Nelson had described domestic challenges as the “greatest of all” in an earlier reflection on the ideal woman of Proverbs 31, she also celebrated the Christian dedication of unmarried women like social worker Jane Addams (a “hopeful idealist” who made the Gospel “a workable reality” through Hull House) and Mary Lyon, founder of the country’s oldest women’s college. “Let us as twentieth century women accept the political, economic, and social challenges,” Nelson had concluded, “as well as the challenges of the church and the home.”9

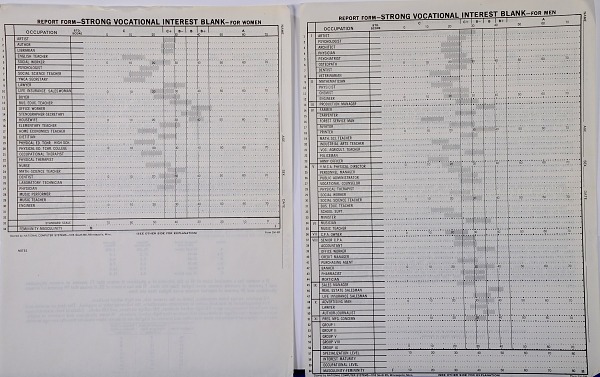

Still, home loomed as large as church in the vocational imaginations of most young women at Bethel in the 1950s. When Nelson and other faculty and staff conducted the College’s first self-study in 1951-52, they had seventy-eight women students and seventy-nine men complete the Strong Vocational Interest Blank (sample below). Overall, those Bethel women rated higher than the national average on that inventory’s “Femininity-Masculinity Scale,” with 72% of them scoring an A rating for housewife. The highest scoring profession for the women respondents was office worker (51%), while jobs like author, lawyer, and physician barely registered; chemist and physicist weren’t even options (as they were on the men’s form).10 It was an era, lamented Smith College graduate Betty Friedan, when “more American women than ever before were going to college—but fewer of them were going on from college to become physicists, philosophers, poets, doctors, lawyers, stateswomen, social pioneers, even college professors.”11

So while Ingeborg (Mrs. Alvin) Sjordal did advise her 1957 audience that “a girl should have some definite plans of her own as to the future — not just waiting for a husband,” she immediately pivoted to a final word of advice: “An ideal girl must make a good wife. She must be able to boil water without burning it and at least know how to set a table. If she can’t do this, she could make it up by being able to sing and play a piano.”12

But if Friedan was right, then the BWA member who took Sjordal’s advice might one day be “afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’” When she published The Feminine Mystique in 1963, Friedan described “a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction” that “lay buried, unspoken… in the minds of American women” who had been taught “that truly feminine women do not want careers, higher education, political rights—the independence and the opportunities that the old-fashioned feminists had fought for.”13 Three years later, Friedan helped found the National Organization for Women, and a second wave of feminism would soon exercise influence and inspire opposition at Bethel.

Feminism and Anti-Feminism in the Era of “Women’s Liberation”

Minnesota became the 26th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment during Bethel College’s first winter in Arden Hills, and the members of Bethel’s honors society in social science debated the ERA in January 1974.14 Two months later The Clarion reported that women in the Midland Terrace apartments were holding “feminars… discussions on the responsibilities of Christian women.” But participant Joan Brand took pains to clarify that she and her friends were “not feminists… People keep asking me about that and it isn’t true.”15 As International Women’s Year ended in December 1975, the Chicago native published an op-ed in Bethel’s student newspaper arguing that

God creates male and female according to His design. We are made to compliment [sic] the man, not to compete with him. Personally, I love being a woman and have no desire to compete. When will we realize that Christ has given us a high place? By accepting our place, we make it our business to understand what our heavenly assignment is and what we are capable of doing now. If it is God’s order for our life to have a career in marriage, then we may do it. We are ordered, however, to fit into the plans and decisions our husbands will make.

Christian women had no need of the women’s liberation movement, Brand concluded, since they were “already liberated… by keeping God’s rules, not breaking them.”16

But other women (and some men) on the Bethel campus were starting to articulate “the other side of the feminism question” — and to question whether traditional gender roles reflected a biblical ideal or Christian conformity to a worldly pattern. Responding to Brand, students Janel Curry and Pam Kramer could “accept the idea that some women are called to be housewives with this as their career, but we also cannot ignore the fact that God has supplied some with certain different talents which they are called to use. This does not mean marriage is given up, but that it can be compatible with a career.”17 After their students in Introduction to Psychology overwhelmingly affirmed that women were responsible for childrearing and men for breadwinning, professors Mike Roe and Glenace Edwall emphasized that the “evangelical community — the Bethel community — should be functioning in its prophetic capacity to break down sex role stereotypes and actively encourage many and unique options to women and men corresponding to their many and unique abilities and gifts.”18

“Are we just here at Bethel to meet ‘wholesome Christian guys’ and eventually find a marriage partner, or are we here to develop our minds and talents so that we can be more effective members of the Body of Christ and propagators of the Kingdom of God here on earth?”19

Anonymous letter to the Clarion editor (1978)

Two episodes illustrate the growing complexity of gender debates at Bethel as the College finished its first decade in Arden Hills. First, the 1977 commencement address by Elisabeth Elliot, the Wheaton College graduate who had famously lived with the Waorani (Auca) people of Ecuador after they killed her husband and four other missionaries.

In 1973 Bethel students attending InterVarsity’s annual missions conference heard Elliot praise women missionaries for pursuing their calling “without the tub-thumping of modern egalitarian movements,” out of quiet, faithful obedience to Christ. “There is nothing interchangeable about the sexes,” she told the 14,000 college students gathered for Urbana 1973. “God has given us gifts that differ.”20 By the time she addressed Bethel’s Class of 1977, Elliot was the best-selling author of Let Me Be a Woman, in which she advised her engaged daughter that the “more womanly you are, the more manly your husband will want to be.”21

At Bethel’s commencement ceremony, Elliot didn’t directly address feminism, but it wasn’t hard to read between the lines. Just as “you belong to a particular anthropological defined race,” she told the Class of 1977, “you are either male or female. And you have no options at all about any of these things.” Rather than protesting that “someone else got what you wanted,” she concluded, “you can accept your offering and gifts and give them back to God as He gave them to you…. It is this body you offer: young or old, tall or short, black or white, whole or handicapped, male or female. Thank God for it, and give it back to him.”22 In one alumna’s memory, Elliot was “telling the women to take their degrees to the home and be good wives and mothers. We wore ERA buttons and a few courageous faculty with tenure walked out in protest.”23

A second episode involved the long-delayed launch of Bethel’s Nursing Department in the early 1980s. Founded by Swedish Baptists around the same time as Bethel Academy, the Mounds-Midway School of Nursing twice explored a merger with Bethel College after World War II. In 1961 consultants advised Carl Lundquist that Bethel should start its own baccalaureate nursing program. After initial attempts foundered in the mid-Seventies, founding chair Eleanor Edman joined the faculty in 1981. Bethel’s first nursing majors graduated in 1984.24

No other curricular or programmatic change did as much to increase the presence and prominence of women on campus. Bethel’s initial proposal to the state of Minnesota anticipated that 90% of the expected 270 nursing majors would be women, pushing the women’s share of the overall undergraduate population close to 60% and prompting planners to consider adding a 3:2 engineering program and men’s ice hockey team to help close the growing gender gap.25 Hiring a department’s worth of nursing professors also raised the women’s share of the College faculty to a historic high: 25% by 1985. But as importantly, adding so many “go-getter nursing faculty” also provided institutional culture with what psychology professor Kathy Nevins described as an “infusion of estrogen,” as “committees became more accomplished” and nursing professors like Edman and Beth Peterson took on faculty leadership and faculty development roles beyond their department.26

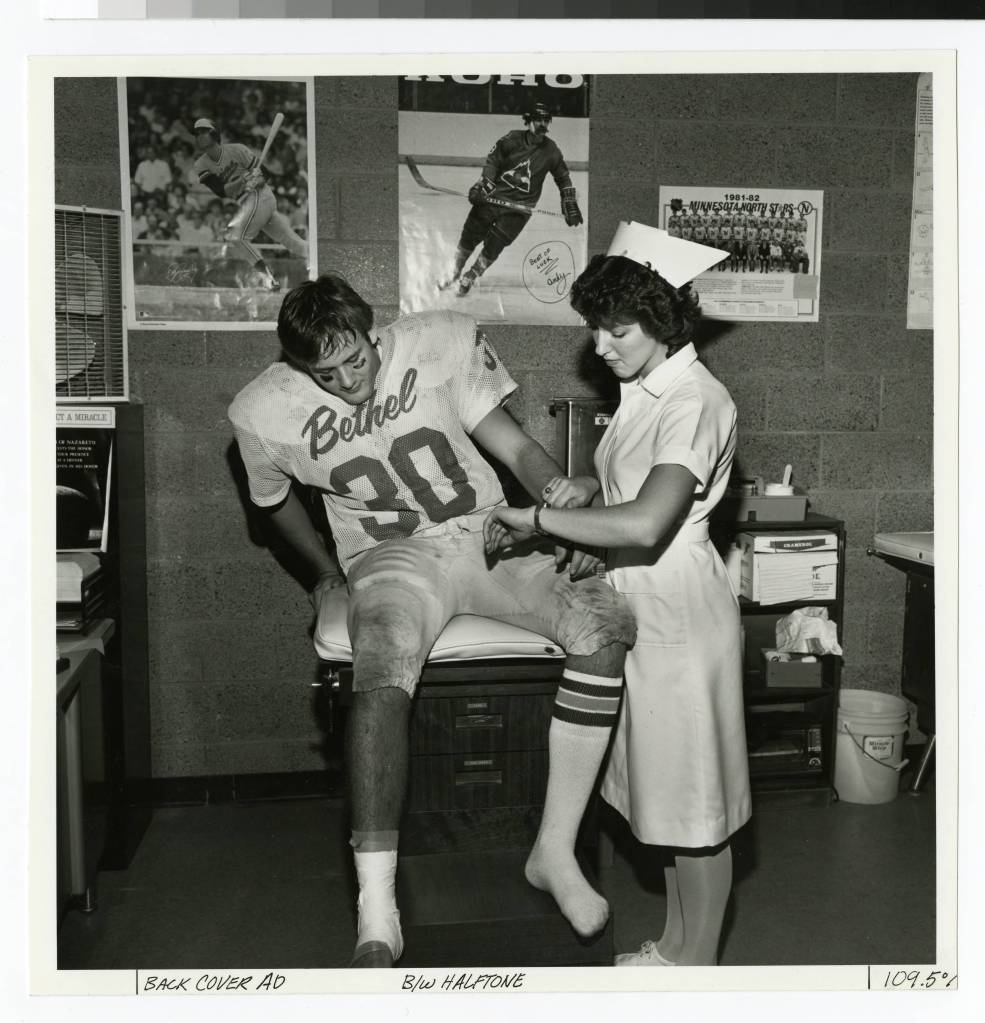

But even as such professors offered their primarily female students new models of Christian women pursuing careers, Bethel struggled early on to know how to publicize their program. Edman recalled that Florence (Oman) Johnson, by then the school’s publications director, asked for feedback on a Nursing Department brochure. “We are not hooking up our students with football players,” Edman told her, after being shown a photo of a nursing major taking the blood pressure of one such student-athlete (below-left). Instead, she remembered the final brochure featuring “a mom and two kids, a toddler and maybe a five-year-old, and a nurse reading something to them in instructions.”27

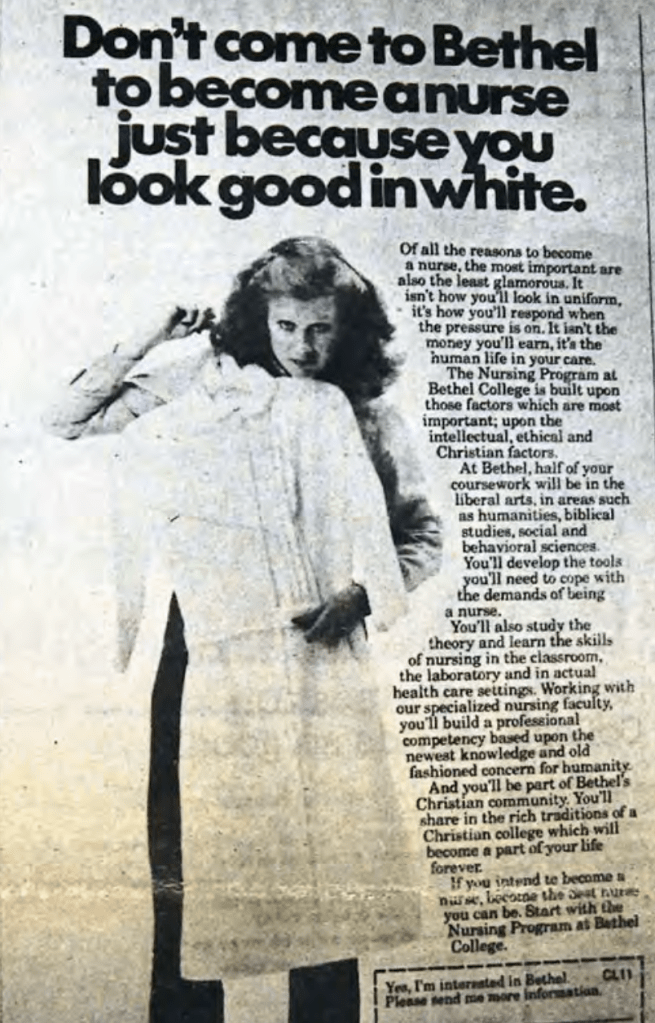

Johnson also received pushback for an advertisement placed in the November 1982 issue of Campus Life magazine (above-right). “Don’t come to Bethel to become a nurse just because you look good in white,” read the headline. “Of all the reasons to become a nurse, the most important are the least glamorous.” Although the ad emphasized learning outcomes and ethical responsibility, nursing students complained in a front-page Clarion story that its image of a blonde woman holding a white uniform was “stereotypical” and “sexist” — just “a small example” of how “sexism is rampant at Bethel,” wrote in another student.28

The Intersection of Gender and Sexuality

Bethel’s student newspaper continued to offer campus feminists an important forum that decade. In 1984-85 The Clarion ran a opinion series on issues rising “out of a growing women’s consciousness,” including English professor Jeannine Bohlmeyer’s critique of sexist language and a student reflection on “sisterhood” inspired by playwright Pamela Carter Joern.29 Just before Christmas 1986 Bohlmeyer told student-reporter Julia Abbott that “feminists are not arguing for female sovereignty or matriarchy, just liberty and justice for all,” while history professor Paul Spickard went so far as to say, “I don’t think you can be an authentic Christian and not a feminist.” Abbott reported that some of those same faculty were in the process of organizing a Women’s Concerns Committee that would advocate for gender equality through policies that we’ll explore in another essay.30

Abbott’s article sparked a furious exchange of letters to the editor, mostly written by men like the freshman who reviled feminism as “a sick and perverted ideology, one that seeks to subvert God’s true intent with a man-made mutation.”31 When psychology professor Mike Roe responded with a defense of Christian feminism, a male education major wondered “why anyone who claims to be a Christian should even want to be associated in any way with a concept which to most Christians generally connotes ideas totally antithetical to Christian faith.”32

Indeed, Abbott had found that many evangelical women shied away from the label of feminist, in part because “feminism has been thrown into the same voodoo pot as secular humanism.” So said Roe’s colleague Kathy Nevins, whose doctoral dissertation had explored the relationship between feminism and conservative Christianity. “When you say feminism,” continued Nevins, “the connotation is radical feminist, lesbian. Right there, you have equated one of the greatest phobias of the church today—homosexuality. But by seeing a feminist as a homosexual you sink your own ship.”33

The growing overlap in debates over gender and sexuality complicated the efforts of evangelical feminists as they defended an egalitarian view of gender roles against complementarian critics like former Bethel professors John Piper and Wayne Grudem. In April 1980, the chair of Bethel’s governing board asked Carl Lundquist to investigate rumors that guest speaker Virginia Mollenkott had “seemed to advocate homosexuality as an alternative evangelical Christian lifestyle.” Two years after she and fellow Christian feminist Letha Dawson Scanzoni published Is the Homosexual My Neighbor?, Mollenkott had limited her convocation addresses at Bethel to the subject of women’s roles, but campus pastor Jim Spickelmier reported that she did take “a more accepting stance on homosexuality than most evangelicals would hold” during a visit to a social work class.34 Spickelmier emphasized that guest speakers had historically offered a mix of viewpoints on gender, as when the College’s chapel service hosted a 1976 series alternating between traditionalist Bonnie Trude and Bethel journalism professor Alvera Mickelsen.35 The latter was then taken aback in 1986 when the Evangelical Women’s Caucus (EWC) passed a controversial motion taking “a firm stand in favor of civil-rights protection for homosexual persons.” Worried that her “ministry to bring the gospel of freedom to women in evangelical churches” would be “diminished by association with a national group strongly influenced by a sub-rosa philosophy and approach that we cannot support biblically,” Mickelsen advised Minnesotan EWC members that Bethel could not host the organization’s 1988 conference as scheduled.36

Mickelsen helped found a new evangelical organization, Christians for Biblical Equality (CBE), which held its first conference at Bethel in 1989 and issued a paper on gender that was signed by several Bethel faculty. That document’s affirmations of “the full equality of men and women in Creation and in Redemption” avoided explicit commentary on political, economic, and social issues and focused on gender roles in the church and family (where it assumed a husband-wife relationship of mutual submission).37 Nonetheless, Mickelsen and other feminists connected to Bethel found it difficult to escape the issue of sexuality. The June 1991 issue of The Standard, the magazine of Bethel’s denomination, the Baptist General Conference, editorialized that evangelical feminism was a model of “faulty hermeneutical principles… If appointed church leaders can twist the Scriptures to approve females as equal to males in headship of home and church, then these leaders can also twist the Scriptures to approve monogamous homosexual/lesbian relationships and the ordination of homosexuals to pastoral service.”38 That The Standard published a rebuttal by Mickelsen and a brief apology in the following issue didn’t satisfy Seminary registrar Florence Walbert, who told editor Donald Anderson that she “found it incredible that you tried to equate the approval of women to head a church with the approval of the ordination of homosexuals.”39

“Lately I have sensed that students at Bethel are tired of hearing about feminism…. In the conservative Christian atmosphere of Bethel, feminists are dismissed as radicals and fanatics. Rather than recognizing the individuality and creativity of each person it is easier to stuff men and women into specific roles.”40

Karen Hill — 1989 student op-ed

Beyond Traditionalism and Feminism: Identity and Curriculum Entering the 21st Century

Thirty-five years after Ingeborg Sjordal told Bethel women that the ideal girl “must make a good wife,” an internal study still found students voicing “the opinion that many Bethel women come to get a ‘MRS’ degree. This can create feelings of being left behind by women who are not in a serious relationship.” While student life vice president Judy Moseman, professors Harley Schreck and Jim Koch, and several student researchers were not surprised to find an American college campus to be “soaked with romance,” they were struck that at Bethel “there is no casual dating allowed. ‘By the third date you are married’ is a stereotype that is generally held.” Participants in their 1991-92 ethnographic research project — whether students, professors, or administrators — assumed that “parents prefer that their children, particularly daughters, attend Bethel in order to find a suitable mate.”41

Even so late in the twentieth century, that preoccupation continued to be “institutionalized in organized activities” like Nik Dag — a Bethel version of Sadie Hawkins’ Day that had debuted in 1948 — and Gadkin, a mid-Eighties addition to the Bethel social calendar that reversed Nik Dag’s tradition of women asking out men. (“Thank goodness the sex roles are exchanged only once a year,” exclaimed a female Clarion columnist after the 1972 Nik Dag.42) The 1992 ethnographic study observed how Gadkin reinforced sterotypical gender expectations: e.g., “Once a woman had been ‘Gadded’, she was required to wear a ribbon in her hair. If she did not she suffered ‘penalties:’ (1) a kiss for the first offense, (2) a dinner out for the second offense, and (3) marrying the man for the third offense.” A Gadkin chapel skit that year “depicted a romance in a 50’s setting. Stereotypes of passive women, aggressive men, and starry eyed love abounded. Men like women who are beautiful. Women like men who are sensitive. The course of romance goes from kissing, dinner together, and marriage—a perfect illustration of stereotypic Bethel dating patterns! All this creates pressure,” leaving women not in relationships often articulating “feelings of inadequacy and self doubt.”43

But at the same time that Bethel’s “hidden curriculum” reinforced older assumptions and expectations, the academic curriculum itself was starting to interrogate gender and investigate the diversity of women’s experiences. English professor Marion Larson recalled coming to Bethel in 1986, at a time when members of her department were starting to pay more attention to “what authors we’re assigning, what issues we’re looking at in class,” out of the conviction that “it shouldn’t just be dead white guys that we were studying.”44 As literature students read Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein in Dan Taylor’s course on modernism, those in the Speech-Communication major explored gender communication with Leta Frazier and nursing majors learned about the experiences of mothers through an upper-level course on childbearing and families. College faculty also started to offer Bethel’s first classes focused entirely on themes of gender. Most enduringly, Kathy Nevins taught a senior general education course called Women’s Lives, Women’s Choices from 1989 until her retirement in 2022. “Female experience is qualitatively different from the male experience,” Nevins wrote in her original course proposal, “yet most academic programs do not acknowledge these differences let alone affirm them as valuable in their own right.”45 Right from the start, Nevins encouraged men to enroll, telling the chairman of the General Education Committee that male students “need to take it more than the women do.”46

Some Bethel students went beyond the curriculum to pursue their own in-depth studies of gender. In 2001 Christina Busman (later Jost) wrote her senior Honors thesis on “Biblical Feminist Theology,” defending it before a committee that included English professor Mary Ellen Ashcroft (author of The Magdalene Gospel: Meeting the Women Who Followed Jesus) and new CBE president Mimi Haddad. Biblical feminists, Busman argued, “are not trying to blend biblical truths with secular feminist convictions nor are they claiming that there are absolutely no differences between a man and a woman.” Without denying either biblical authority or biological distinctiveness, she rejected “the dominant theology in the history of the church… that has oppressed women and viewed them as inadequate and incomplete” and instead advocated a theological method that aimed at “the emancipation of God’s children, the move to fully accept every sister and brother in Christ, and the spreading of God’s kingdom.”47 After studying at Princeton Theological Seminary, Busman returned to Bethel in 2008 as the first woman to serve as a theology professor in what had been renamed the College of Arts and Sciences.

By then, the Bethel University Feminist Forum (BUFF) had become an officially recognized student club, succeeding an earlier, informal group called Biblical Gender Consciousness.48 While BUFF co-leader Celeste Harvey told The Clarion in 2005 that Christian feminists affirmed women’s domestic roles and their traditional work in careers like nursing, education, and social work, she hoped that the new club would “encourage more women in the Christian world to consider whether they could be fulfilled outside the home.”49 Harvey majored in philosophy, a department that had just added the first woman to its full-time faculty: Sara Shady, who taught a seminar on feminism and later developed an introductory course in gender studies.

After several years of faculty debate, a minor in that emerging field entered the CAS catalog in 2013-14. College faculty had first talked about the need for a “women’s studies” program when the Women’s Concerns Committee began to organize in 1986.50 But when it finally came into being, the gender studies minor looked well beyond the earlier debates over women’s roles. “When I started teaching Intro to Gender Studies, students would get really fired up about women in leadership in the church kind of issues and the complementarian vs. egalitarian debate,” Shady recalled in a 2024 interview. “And now most students are kind of indifferent to that or they don’t see it as relevant anymore. What students now are really interested in more is the actual gender side: understanding what it means to be trans or gender-fluid or non-binary. And how are Christians supposed to navigate those terms and those identities?”51 From the beginning, the other required course in gender studies was AnneMarie Kooistra’s on the history of sexuality, and the minor’s list of elective options came to include a course on masculinity taught by another history professor, Charlie Goldberg.

As we move from Bethel past into Bethel present, it was also striking to find that while several of the current students and recent graduates I interviewed for this project still wrestled with the connotations of the terms feminism and feminist, all affirmed a far greater range of roles and norms for women than what previous generations would have known. Gretchen Mugglin, a psychology and history major active in Bethel student government, acknowledged that she probably wouldn’t introduce herself as a feminist, but only because “it’s not a trait as much as it is a nutrient in the soil my beliefs take root in. When people ask me if I’m a feminist I say, short answer, yes. I have deep seated beliefs that women and men are meant to be equals, and are equals in God’s eyes. Imago dei applies to everyone.”52 Spanish immersion teacher Micayla (Moore) Franklin ’16 recalled learning that phrase — Latin for “image of God” — at Bethel, where she “came to know and trust that God loves me as the woman I am, that there isn’t just one way to be a good Christian woman.”53 While Franklin and Mugglin accepted the term feminist, Naomi Henderson came to find aspects of feminism unhelpful, as a Christian who is “passionate that women not be discounted because of their gender.” A 2024 graduate in both math education and music education, Henderson wanted to see women “allowed to exercise their gifts and skills wherever the Lord has them,” but she rejected some feminist language (“flip the patriarchy”) and what she sees as “the independent or victim mindset often associated with feminism.”54

Knowing that the term still connoted “anti-male” for many at Bethel, Kathy Nevins defined feminist in a 2024 interview as someone who “believes that women are people, too.” In the end, she was much less concerned that Bethel faculty “self-identify as a feminist” than that they “be supportive of the aspirations of the women… [they] come in contact with.”55

Introduction | Debating Gender | Women in Ministry | Policies and Persons

Women and Sports | Conclusion

NOTES

- “My Ideal Girl” talks, preserved in “Effie V. Nelson file-Deanship of Women,” Roy C. Dalton Papers, Box 1, The History Center: Archives of Bethel University and Converge (hereafter HC). For a brief announcement of that event, see The Clarion, March 12, 1957, 4. ↩︎

- “My Ideal Girl” talks. Emphasis original. ↩︎

- Letter, Florence Oman to Effie Nelson, October 1, 1962, Effie Victoria Nelson Papers, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- 1963-64 study by sociology professor David O. Moberg and students, Carl H. Lundquist Papers, Box 3, HC. Incidentally, Moberg’s wife, Helen, had been another of the “Ideal Girl” speakers. ↩︎

- “My Ideal Girl” talks. Emphasis original. ↩︎

- Bethel College, 1956-56 Catalog, 29. ↩︎

- Bethel College and Seminary report to Baptist General Conference (BGC), 1953-1954 Annual, 106. ↩︎

- Program for Bethel Women’s Association Commencement Tea, May 22, 1960, in Women’s Dormitory Council Collection, Box 2, HC. ↩︎

- Effie Nelson, “A Challenge to the Twentieth Century Woman” undated [ca. 1940?], Nelson Papers, Box 2, HC. For more on Mary Lyon and what Nelson called her “spiritual values,” see Andrea L. Turpin, A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1837-1917 (Cornell University Press, 2016), ch. 2. ↩︎

- Just under 50% registered an “A” for elementary school teacher, about a third for stenographer or secretary; Bethel College, 1951-1952 self-study for North Central Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges, Dalton Papers, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, 50th anniversary edition (W.W. Norton, 2013; original, 1963), 171. ↩︎

- “My Ideal Girl” talks. Emphasis mine. ↩︎

- Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, 1-2. Emphasis mine. ↩︎

- The Clarion, January 11, 1974, 2-3. ↩︎

- The Clarion, March 8, 1974, 4. ↩︎

- The Clarion, December 12, 1975, 3. ↩︎

- The Clarion, January 16, 1976, 2. ↩︎

- Michael D. Roe, Carol M. Kramer, and Glenace E. Edwall, “Sex Role Stereotyping is Alive and Well… Unfortunately,” Bethel Faculty Journal, November 1978, 9. Note that digital access to this journal is limited to Bethel community members on campus. ↩︎

- The Clarion, October 13, 1978, 2. ↩︎

- Elisabeth Elliot, “Women in World Mission,” address to Urbana 1973 conference. (The link is to an audio recording available on YouTube.) One Bethel eyewitness to that talk didn’t mention Elliot’s comments about gender, but did appreciate how she shared her “unwavering simplistic trust in the Lord” after the deaths of both Jim Elliot and her second husband, theologian Addison Leitch; The Clarion, January 25, 1974, 2. ↩︎

- Elisabeth Elliot, Let Me Be a Woman (Tyndale House, 1976), 149. For more on Eliot’s long life and complicated legacy, see Lucy S.R. Austen, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life (Crossway, 2023). Ch. 10 is most pertinent to her 1977 visit to Bethel. ↩︎

- Donna Otto read a transcript of Eliot’s May 22, 1977 commencement address at Bethel on the October 6, 2017 episode of her podcast, Modern Homemakers. Emphasis mine. ↩︎

- Lynn Baker-Dooley, email interview with author, October 9, 2024. Note that all email and oral history interviews from 2024-25 are quoted by permission of the interviewees. ↩︎

- For more on the founding of the Nursing Department, see my blog post of November 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Baccalaureate nursing program proposal to Minnesota Higher Education Coordinating Board, November 9, 1979, 19, in Bethel Reports Collection, Box 22, HC. After the program’s first decade, the share of men in the undergraduate program was around the 10% originally projected; 1995 Nursing Department self-study, Bethel Reports Collection, Box 23, HC. In Bethel’s most recent report to the U.S. Department of Education, men accounted for 12% of bachelor’s degree recipients in Nursing and 8% of those earning graduate degrees in that field; Bethel University, 2022-23 reported data, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National Center for Education Statistics, accessed July 6, 2025. ↩︎

- Kathy Nevins, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, June 24, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. The Nursing faculty added Dave Muhovich (1995) and Tim Bredow (1998) during its second decade; as of the summer 2025 writing of this essay, Muhovich is the only male professor in the department. ↩︎

- Eleanor Edman, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, June 28, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- The Clarion, November 12, 1982, 1; Cindy Oberg, letter to the editor, The Clarion, November 19, 1982, 2. ↩︎

- Respectively, The Clarion, November 16, 1984, 6, and November 30, 1984, 6. ↩︎

- The Clarion, December 12, 1986, 10. ↩︎

- Jay Johnson, letter to the editor, The Clarion, January 23, 1987, 4. ↩︎

- Mike Roe, letter to the editor, The Clarion, February 13, 1987, 4; Neal Harris, letter to the editor, The Clarion, February 27, 1987, 4-5. ↩︎

- Katherine Juul Nevins, “Personality Correlates of Christian Feminists, Religious Fundamentalists and Feminists” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1986); The Clarion, December 12, 1986, 10. As if to illustrate her point, the Harris letter cited above insisted that feminism required “an acceptance of the homosexual lifestyle as normal and legitimate.” ↩︎

- Memo, Carl Lundquist to George Brushaber, April 21, 1980, and memo, Jim Spickelmier to Lundquist, April 23, 1980, Carl H. Lundquist Papers, Box 33A, HC. See also John Piper’s response to Mollenkott’s convocation address, in which he warned that her interpretation of Galatians 3:28 risked condoning “even committed homosexuality”; letter to the editor, The Clarion, May 9, 1980, 3. ↩︎

- “We won’t try to harmonize them [the speakers’ perspectives] but have them tell what their positions are and let the disagreement be apparent,” Spickelmier had explained before the Trude/Mickelsen Chapel series; The Clarion, November 5, 1976, 7. ↩︎

- Letter from Alvera Mickelsen, published in August 1986 newsletter of the Minnesota chapter of the Evangelical Women’s Caucus, in Katherine Nevins Papers, Box 3, HC. ↩︎

- CBE International, “Men, Women, and Biblical Equality,” adopted 1989. For more background on this debate, see Pamela D.H. Carson, Evangelical Feminism: A History (New York University Press, 2005), ch. 4. ↩︎

- “Hermeneutics,” The [BGC] Standard, June 1991, 35. ↩︎

- Letter, Florence Walbert to Donald Anderson, September 18, 1991, The Standard Collection, Box 4, HC. Walbert pointed out that the original editorial was on the reverse page of a photo showing former Standard editor Martin Erikson, who had sponsored the historic ordination of Bethel Seminary graduate Ethel Ruff in 1943: “It is hard to conceive of your predecessor as approving ‘monogamous homosexual/lesbian relationships and the ordination of homosexuals to pastoral service’ because he endorsed the ordination of Ethel Ruff to the Gospel ministry.” You’ll find the full story of Ruff’s ordination at the beginning of my essay on women in ministry. ↩︎

- The Clarion, March 10, 1989, 5. ↩︎

- Harley Schreck, Judith Moseman, Jim Koch, et al., “Bethel Student Culture: an Ethnographic Study of Bethel College Students,” April 10, 1992, in Bethel Reports Collection, Box 28, HC. The quotations come from pp. 27-31. ↩︎

- “Girls Treat Boys To Nikolina’s Dag,” announced the front page of The Clarion, November 23, 1948; the “sex roles” quotation comes from The Clarion, December 8, 1972, 7. By 1989-90, Nik Dag had moved to the spring, while Gadkin took over its November place in the annual calendar; The Clarion, October 27, 1989, 2. ↩︎

- “Bethel Student Culture,” 27, 29, 31. ↩︎

- Marion Larson, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, July 16, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. Another woman in the same department, Jeannine Bohlmeyer, dedicated the last sabbatical before her 1988 retirement to reading women writers typically left out of literature courses and anthologies; she reported on that project in “Review of Women Writers,” Bethel Faculty Journal, Spring 1988, 32-42. ↩︎

- Kathy Nevins, draft course proposal for “Women’s Lives, Women’s Choices,” October 3, 1988, Nevins Papers, Box 3, HC. ↩︎

- Nevins oral history. For a deeper dive into gender in the Bethel College curriculum, see my blog post of December 9, 2024. ↩︎

- Christina Busman, “Biblical Feminist Theology: Toward a Methodology,” 2001 Senior Honors project, Honors Program Collection, Box 1, HC; quoted by permission. DesAnne Hippe began teaching theology at Bethel Seminary in 2003. ↩︎

- The Clarion, October 8, 1993, 7. ↩︎

- The Clarion, October 6, 2005, 2. ↩︎

- Minutes of ad hoc Committee on Women’s Concerns, May 14, 1986, Files of Women’s Concerns Committee, HC. ↩︎

- Sara Shady, oral history interview with Christopher Gehrz and Ellie Heebsh, July 30, 2024, Women of Bethel Oral History Collection, Box 1, HC. ↩︎

- Gretchen Mugglin, email interview with author, January 23, 2025. ↩︎

- Micayla Franklin, email interview with author, January 10, 2025. ↩︎

- Naomi Henderson, email interview with author, January 19, 2025. ↩︎

- Nevins oral history. ↩︎