In addition to teaching undergraduates at Bethel, I also enjoy frequent chances to teach adult students at churches, senior living communities, libraries, museums, and other sites. Since they tend to meet just once or twice, one of my favorite ways to structure those adult classes is to offer a survey of a larger topic via a shorter list of “turning points.”

It’s an approach I learned from Christian historian Mark Noll, who first used it in teaching a church history survey at an underground church in Ceausescu-era Romania. Unable to carry more detailed materials into the still-Communist country, he jotted down a course outline in the form of a few bullet points, and realized that it was actually a good way to introduce new students to the complexity of history — telling those few stories to introduce what came before and after. His book on turning points in the global history of Christianity is now in its 4th edition, and it recently inspired Elesha Coffman to deploy a similar strategy with American church history.

So when we were setting up our oral history project last summer, Ellie Heebsh, Sam Mulberry, and I thought it would be a good idea to ask each participant in the more in-depth interviews of our first phase if she would identify one or two turning points in the women’s history of Bethel. They listed a wide range of events, some expected and some not.

For example, I wasn’t surprised that two women mentioned the creation of the gender studies minor in 2013, though neither elaborated very much on that curricular change. But I was surprised that only one interviewee reflected at length on Title IX marking a key transition for Bethel: former physical education professor-turned-academic dean Tricia Brownlee, who pointed out that she founded the women’s volleyball and softball programs a few years before that 1972 legislation. We did happen to interview the current coaches of those two teams, Gretchen Hunt and Penny Foore, but they had less to say about the institutional impact of Title IX than what it meant for their individual development as youth and college athletes.

Here then are the most common turning points named by multiple interviewees:

Deb Harless becoming provost in 2013

No event was named more often than former psychology professor Deb Harless filling the second-highest position in American university hierarchies. “I think I kind of took it for granted that, ‘Well, she’s qualified, so of course, you should get it.’ So I’m just naive that way, perhaps,” recalled Deb Sullivan-Trainor, who succeeded Harless as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “I think it finally did dawn on me, especially with the fact that the Seminary would be supportive and okay with a woman provost was important.”

As it happened, Harless was one of the last women we interviewed, so I had the chance to point out just how frequently her appointment as provost had been mentioned by others. “Honestly, I think I was more conscious of being a Bethel alum in that role,” she responded. “I think maybe it’s because I had been an administrator already for a dozen years before that. But I don’t know if I thought a lot about it in terms of being a woman, but I did think a lot about it as being a Bethel alum and being someone who was the first person in their family to get a four-year college degree. I think for me personally, those were things I thought more of.” While I wasn’t surprised that Harless would downplay the significance of her own promotion, it’s worth noting that English professor Marion Larson, who had been on the committee that recommended Harless as provost, also thought that her being the first woman in the role “was irrelevant to the choice. In that particular case, we had narrowed it down to three people, and all three of those people were already employed here. And two were women, Deb obviously being one of them.”

So this may be less of a distinct turning point than the culmination of a longer trend. Other interviewees mentioned Brownlee moving from athletics/physical education to academic affairs and eventually becoming dean in that area, and current vice president of student experience Miranda Powers pointed to her predecessor in that area, Judy Moseman, as the first Bethel woman to hold the title of vice president. “I think every time a woman is promoted and given the opportunity to lead, it’s an encouragement to other women who are on staff,” said Sherie Lindvall, who joined Moseman on the cabinet as head of communications and marketing. “Making the decisions that both President Brushaber and President Barnes made in putting women in key roles of leadership were important times… or transitional times, institutionally.”

Laurel Bunker becoming campus pastor in 2008

George Brushaber also hired Sherry Bunge (later Mortenson) in 1985 as director of discipleship, a title that changed to associate campus pastor six years later. “Before I was coming to Bethel, I was trying to get my head around what really is their approach to women?”, said Sullivan-Trainor, who joined the Modern World Languages department in 1999. “When Sherry became campus pastor, that made a big difference. I mean, in a denomination that has various levels of conservatism in it, for there to be a woman pastor is, was actually huge.”

Incidentally, Mortenson didn’t identify her own hire as a turning point, though she did recount encouraging two students, Mary Sue Beran and Amy Sharman, to launch Bethel’s popular Vespers worship service. Instead, she (like several others) pointed to another landmark appointment in campus ministries at Bethel: the 2008 hire of Laurel Bunker as the first woman to serve as head campus pastor and dean (later vice president) in that area. Larson put the two appointments together: “Honestly, given the perspective of some people in Converge and in some of the other churches and denominations that are connected with Bethel, I was really surprised that Sherry Mortenson was in Campus Ministries and that Laurel Bunker was in Campus Ministries. I don’t know what kind of battles had to be fought behind closed doors about that. But I know that both of those two women were criticized simply because they were women and they were preaching.”

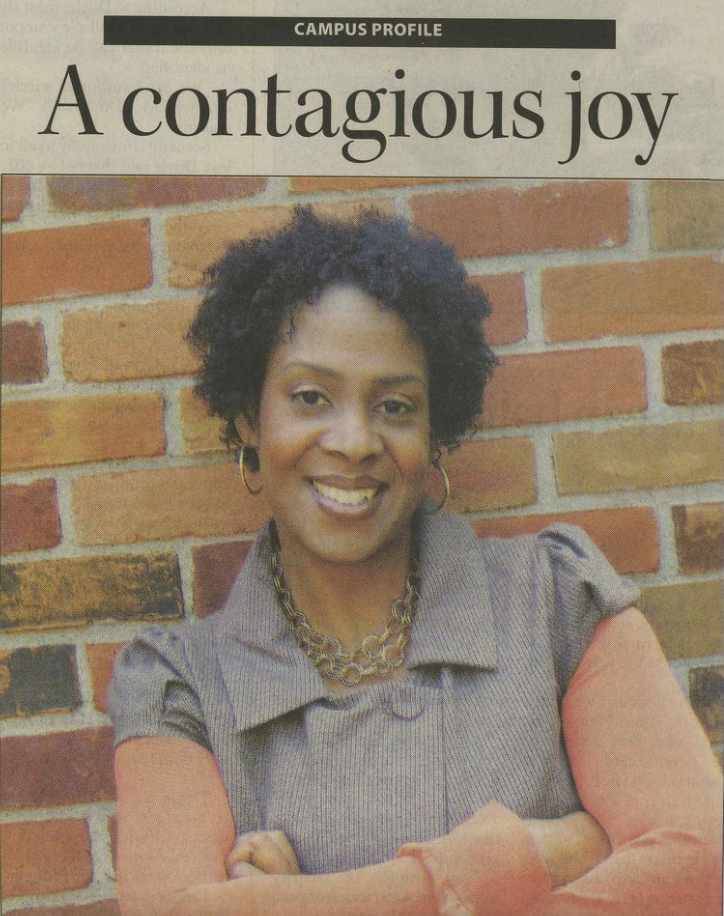

Of course, Bunker’s hire was also significant as marking a key breakthrough for persons of color on staff: she was also Bethel’s first (and so far, only) African American campus pastor. Here too, interviewees underscored the importance of leadership from the president’s office. “The inauguration of Jay Barnes” heralded a new commitment to diversity, said former associate campus pastor Donna Johnson, as in “the hiring of Pastor Laurel. That was huge, and he was taking a huge risk to do that.” For her part, Bunker emphasized that “Jay really valued diversity and that included women in leadership. And he supported us deeply.”

Likewise, Deb Harless underscored that Barnes’ cabinet included not only her, but “several women in senior leadership. We had a woman who was a CFO [chief financial officer]. We had me as the Provost. We had a… chief human resources officer that was a woman… So that was a noticeable transition for me, where we had women in really senior leadership positions. And it was still a time where a lot of our sister schools didn’t have many women in leadership, and they certainly didn’t have a woman provost or a woman CFO. So that was a transitional moment that was really noticeable to me.” In this respect, Harless thought that Bethel benefited from the creation of a women’s leadership initiative at the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities, in which she participated and to which she later recommended other Bethel women.

Carla Dahl and Jeannine Brown joining the Seminary faculty in 1995 and 2000

Given Bethel’s Midwestern culture, I fully expected interviewees to resist centering themselves in stories of historical transitions. But I was glad that the two Seminary professors we were able to interview were willing to talk about their own hires as turning points, since there had been only two women on the Seminary’s full-time faculty before 1995.

Carla Dahl, whose appointment to head a new program in Marriage and Family Therapy was debated at the 1995 Baptist General Conference annual meeting, agreed that her hire was a turning point,

not because of me, but because it was now okay to have women on faculty. And then we suddenly got more: Jeannine Brown and Denise Muir Kjesbo and, you know, DesAnne Hippe. We just kept kind of getting more. And it was really fun to have that kind of mix in the conversations and faculty meetings, being able to think about the future of the Seminary with several people who had different perspectives and different passions. And there’s a woman professor in each center at that point. So I think that was important, a very strong transitional moment, not because of me but because of the courage it took to hire a woman and then to also appoint that woman as dean of the center. That was a big deal.

For her part, New Testament professor Jeannine Brown was able to put her 2000 hire in historical perspective, having been a student and adjunct instructor at the Seminary. “I remember when I was a student in, what, probably 1989, they were looking for a woman and were having a hard time finding a woman who fit,” she told us. “So I know they’d been trying for over 10 years to hire, and so when they started to meet with me… it would be an internal hire. It would be somebody who was a known quantity… It just was a hard process for that to happen.”

Women had been part of the College faculty since it was founded as a two-year program in 1931. But a later hire on that side of the institution came up in several interviews. The founding chair of the Education Department, Junet Runbeck may have been the first woman professor in Bethel history to hold a doctorate when she was initially hired, in 1962. “And she had worked hard for that,” added Carole Lundquist Spickelmier, who worked as an English teacher after graduating from Bethel in 1964. “She was a tough teacher. And all of us who took class from her share stories sometimes about how she came down kind of hard on us and said, ‘You’re not doing your best work. I know you can do better.’ I know she did that for me a couple of times. And it was not fun, but it was true. And I tried to shape up more for her work.” Runbeck modeled the hard work ethic that she demanded of students. Judy Moseman “had utmost admiration for her,” having both studied under Runbeck and worked with her in the Education Department. “I saw her working sacrificial numbers of hours with the lights turned on at the Education house on the Old Campus as she developed that entire program before it was accredited” in 1968.

The launch of the Nursing Department in the Early Eighties

Likewise, we’d already invited Eleanor Edman, founding chair of the Nursing Department, to take part in our project because we knew that program’s launch to be a significant moment in the women’s history of Bethel. “It just gave numbers and strength to the women on the faculty,” said Tricia Brownlee, “and they had then more women students, too.” But I also appreciated what psychology professor Kathy Nevins told us about the impact so many nursing professors had beyond their department:

What that did was infuse the faculty with these go-getter nursing faculty — mostly women, not all, but mostly women — who were led by Eleanor Edman, who wanted her departmental faculty to be actively involved in the entire school. And so, they were. And it was an infusion of estrogen in a way that I think sort of got people off their bums and doing things, right? Committees became more accomplished, I think, in the work that we did. Things were thought through, things were more organized; things didn’t sit, you know, on the back shelf for two, three, four, X number of years. They got taken off the shelf. They were great at getting things done.

Here too, the particular hire of Edman in 1981 may point to a larger shift in that era. “I would point to the 1980s as the time when the tide changed for women,” said Spickelmier, whose multiple connections to Bethel start with her father’s hire as president in 1954. “Up till then, almost all were single or had support roles. And after that, there were many women who were coming to apply for jobs. And at that point, they had had enough time. I’d say that my generation, many of them went on and got further degrees, and so they were ready to take on roles in a college or seminary that maybe the others hadn’t really been quite prepared for.”

While single women continue to play key roles at Bethel to this day, one important theme in my final project will be the growing prevalence of working mothers on faculty and staff. So I was glad that math professor Patrice Conrath discussed not just changing policies for such employees, but her memory of serving as maternity advocate — most poignantly, when she helped anthropology professor Jenell Williams Paris through the sudden loss of her pregnancy: “We had a little service for her up at the Scandia Chapel… and it was so neat to see people affirming her and helping her through that. It was like these places where people began to affirm a woman as a whole person, recognizing that they were an academic. They also had this part of their life, not ignoring that part of their life, but bringing that into the picture of the whole person.”

What do you see as turning points in the women’s history of Bethel University? If you want to add something to the list or reiterate an earlier nomination, please use the comments section below.

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.