Early on this project, I reflected on the value of photographs as historical evidence, which “can be especially significant in answering historical questions on which other evidence is silent.” But while I’ve incorporated several such images into blog posts, digital timelines, and the final essays I’ve been working on this summer, they’ve served more as visual embellishments to text, not so much sources in their own right.

So before I start drafting the last essay I have in mind, I thought I’d try an experiment. What would it look like if one sketched Bethel’s history of women’s sports in the 20th century simply by curating one or two photos per decade, moving from Bethel yearbooks to student newspapers as the former grew more impressionistic and intermittent (ceasing publication entirely in 1989) and the latter started to include more images?

While the present-day Athletics Department can regularly boast of All-Americans and conference championships, the sports history of Bethel University began far more humbly. On its older campus in the St. Anthony Park neighborhood of St. Paul, Bethel Academy lacked a gymnasium, and editors of the 1910 edition of the The Acorn lamented “that we have not the material for working up a first class baseball nine.” Such shortcomings, they had complained the year before, limited Bethel’s ability to live up to the admirable motto of the Young Men’s Christian Association: “Mind, body, and spirit. This motto, if followed up closely, will give us a perfect man as far as man can be perfect,” yet its lack of athletic facilities denied Bethel Academy students “an opportunity to develope [sic] this phase of a man…”

Still, students boxed and wrestled in a classroom and played hockey on the frozen surface of a nearby pond. Then each spring they marked off a tennis court on the same lawn that hosted impromptu football practices in the fall. Despite the gendered language of developing the “perfect man,” mixed doubles tennis was one sport where young Bethel women could develop their bodies, in addition to their minds and spirits.

When the new Academy building went up on the Snelling Avenue campus in 1916, it included a 72×42 foot gymnasium that hosted compulsory physical education classes for both sexes. “Boys and girls have separate entrances with equal shower facilities,” explained the 1922-23 Academy catalog, “and use the gymnasium on alternate days.” That year’s Bethannual photographed the girls drilling indoors in “marching, wand and Indian club,” and noted that fall and spring took them outside for such activities as “hiking, kitten ball [a precursor to softball] and volley ball.”

Bethel Academy had had intramural girls’ basketball teams since at least 1916, but it wasn’t until 1923 that the yearbook recorded any competition with another schools (two losses to Minnehaha Academy). In 1936-37, the first year Bethel Institute included the Junior College but not the recently closed Academy, that team comprised the only women depicted on the Depression-shortened yearbook’s two athletics pages, which showed men playing baseball, basketball, golf, horseshoes, and tennis.

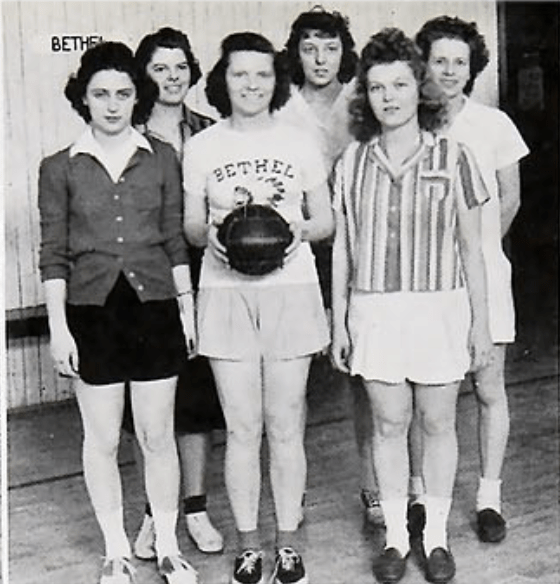

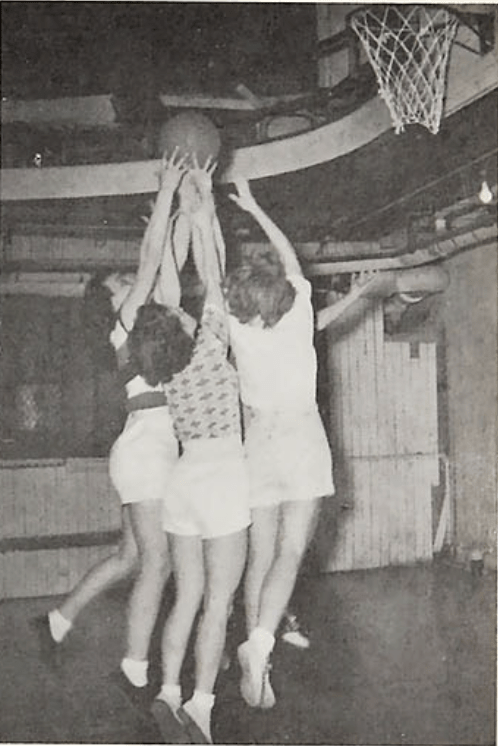

But I’ll instead show you the photos from the following year’s Spire, which includes the typical team shot (with Bill Adam, who coached men and women) above four individual poses and a trophy earned in a 12-7 victory over the Twin City Church League all-stars (according to the March 1938 issue of The Clarion). Until the early 1970s, women’s basketball generally followed rules laid out around the turn of the century by Senda Berenson of Smith College, which limited dribbling and physical contact and restricted players to one section of the court. “Unless a game as exciting as basketball is carefully guided by such rules as will eliminate roughness,” wrote Berenson in 1903, “the great desire to win and the excitement of the game will make our women do sadly unwomanly things.”

“Competition sharpens skill and quickens interest,” proclaimed the 1941 Spire — and not just competition with other collegiate teams. By the 1940s, intramural squads of men and women were competing in volleyball, basketball, and softball, and archery was being tried out in gym class tournaments. That last yearbook published before the U.S. entered World War II didn’t mention if women also played in horseshoes and ping pong, “ex-officio sports” that “occupied hours of time that perhaps could have been more profitably spent on studies — but much less enjoyably.”

Spurred by the 1947 launch of the four-year college and an influx of military veterans using their G.I. Bill benefits, Bethel sports expanded significantly entering the 1950s, adding a new field house, a long-delayed football program, and the college’s first dedicated athletics director position. In addition to football, basketball, and baseball, male students in the 1950s could go out for golf, tennis, track and cross country, and even — for a short period commemorated by some amazing photos — gymnastics.

Basketball remained the only intercollegiate women’s sport until the late 1960s, but the advent of Bethel football also initiated the on-and-off history of Bethel cheerleading. While the fledgling program was initially coed, The Spire reported that the “several fellows” who started the 1950-51 year on that team “were unable to keep up their duties”; men didn’t rejoin the squad until the mid-Sixties. It was one of many early challenges confronting the Royal Rousers (originally Royalettes, though that term was soon applied to basketball players). After male students jeered them during their first year, The Clarion offered a kind of defense of Bethel’s cheerleaders: “It is obvious that they are not performing for their health’s sake. Let’s cooperate with them and yell, being equally enthusiastic throughout the entire game.”

Even in the decade before Title IX was enacted, the addition of women to Bethel’s physical education faculty led to new athletic opportunities in and out of the academic curriculum. Marilyn Starr introduced a women’s canoeing trip in 1961-62, but the most consequential appointments were those of Carol Morgan, who took over the women’s basketball team and started a short-lived field hockey program in 1967, and Tricia Brownlee, who joined the faculty in 1968 and would go on to become the first woman to serve as academic dean at the College. “When I came my first year,” Brownlee recalled, “I started volleyball and softball. And it was like pulling teeth to get access to the facilities, or to get any budget.”

Many girls share this same enjoyment of competition and sports which, in our society, seems characteristic only of men. Unfortunately, however, the majority of girls remain as spectators and for the most part do so from the lack of opportunity to play and to become proficient enough to enjoy a game or sport.

Carol Morgan, 1971-72 yearbook

Inadequate budget and facilities would remain a theme of women’s sports at Bethel throughout the Seventies. But by 1971-72, the College’s last year on the Snelling Avenue campus, Brownlee and Morgan had secured state approval for a full-fledged major in physical education, which recruited new student-athletes who prepared for careers teaching and coaching girls in an even longer list of sports (e.g., bowling, golf, gymnastics, soccer, tennis).

While coeducational teams had never been absent from Bethel athletics, thanks to mixed doubles play in recreational racquet sports like tennis and badminton, handbooks from the late Seventies and early Eighties suggest a more intentional effort to mix women and men in the intramural program. The 1977-78 handbook required that “50% of the players must be girls” in coed volleyball, and “hits MUST be alternated between men and women.” Evenly mixed teams were also required in coed basketball, where “each sex much touch ball before shot can be taken” and “girls standing on men’s shoulder’s [sic] is permissible (on offense only).” Then there’s Bethel’s most enduringly popular mixed-gender sport…

The Clarion mentions broomball as a Bethel student activity as early as 1960, but a competitive tournament in that sport only became a January-term tradition in the mid-1970s, with games held on Lake Valentine by 1974 and coed broomball entering the intramural handbook in 1977. The Clarion reported that the women on the 1979 champions, the Butchers, “constantly frustrated the Family’s high-scoring forwards in their attempt to organize an offensive attack.” By 1981, rules had changed to require that the five players taking a tie-breaking shootout include “at least 2 girls.”

Not surprisingly, given Bethel’s historic lack of facilities and other athletics resources, some sports did come and go: gymnastics for men; field hockey for women. But while women’s athletics had expanded by 1981 to include track and tennis, it suffered a major blow four years later with the closure of one well-established program. Victims of Bethel’s economic challenges during the Baby Bust years, both women’s softball and men’s wrestling were cut in 1985 to help bring down Athletic Department costs. “Any time you eliminate a sport, you’re eliminating potential students,” admitted athletic director George Palke in 1988. “However, in choosing to drop these sports, we sought to determine how the fewest people would be affected, while still making significant dollar savings.”

A club team revived in 1993, then varsity softball returned the following spring under head coach Pam Wolf, a pitcher and shortstop on the 1985 team. In more recent years, Bethel softball has won conference championships and competed in the NCAA tournament, but current head coach Penny Foore acknowledged in her oral history interview that the nine-year interruption in the program’s history did have a lingering impact on “building relationships and donors.”

It was only in the 1990s that Bethel made a concerted effort to meet Title IX’s gender parity expectations for sports, increasing budget and staffing for women’s athletics. While the college’s final NCAA report of the decade made clear that there were still deficits — e.g., Bethel still spent about as much on football in 1999-2000 as on all women’s sports put together, women accounted for 40% of all student-athletes by the end of the twentieth century, competing in a list of sports that had grown to eight with the restoration of softball and the additions of soccer (1993) and ice hockey (1999 — golf would round out the current list in 2008-09).

Those programs still collectively accounted for just one-eighth of the department’s recruiting budget at the end of the 1990s, but women’s sports were starting to achieve the on-field successes that are now typical of the program. Or rather, on-court: the first women’s team to win a MIAC championship was the 1993-94 basketball squad. Coached by Deb Hunter, an All-American at the University of Minnesota in her own playing days, the Lady Royals finished the regular season 20-4 and made it to the Elite Eight of the NCAA tournament. Sharp-shooting guard Vickie Estrellado (later Seim), who also helped lead the team to the Final Four in 1996, recalled feeling “fully supported as a student-athlete at Bethel, especially because our basketball was very successful. The entire community was always cheering for us. It was an amazing experience because it seemed that everyone was involved (students, parents, professors, other sports teams)…. There was so much hype and energy surrounding our games!”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Today I’d especially be glad to read some reminiscences and reflections about women’s sports. Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.

Chris, I just want you to know that I really enjoyed reading this. I passed it on to Athletics and they enjoyed it as well!

Thanks, Miranda Miranda Powers, M.A. LPC Vice President of Student Experience| Bethel University m-powers@bethel.edu | 651.635.8776

LikeLike

Thanks, Miranda! I’m looking forward to fleshing this out for the final version.

LikeLike