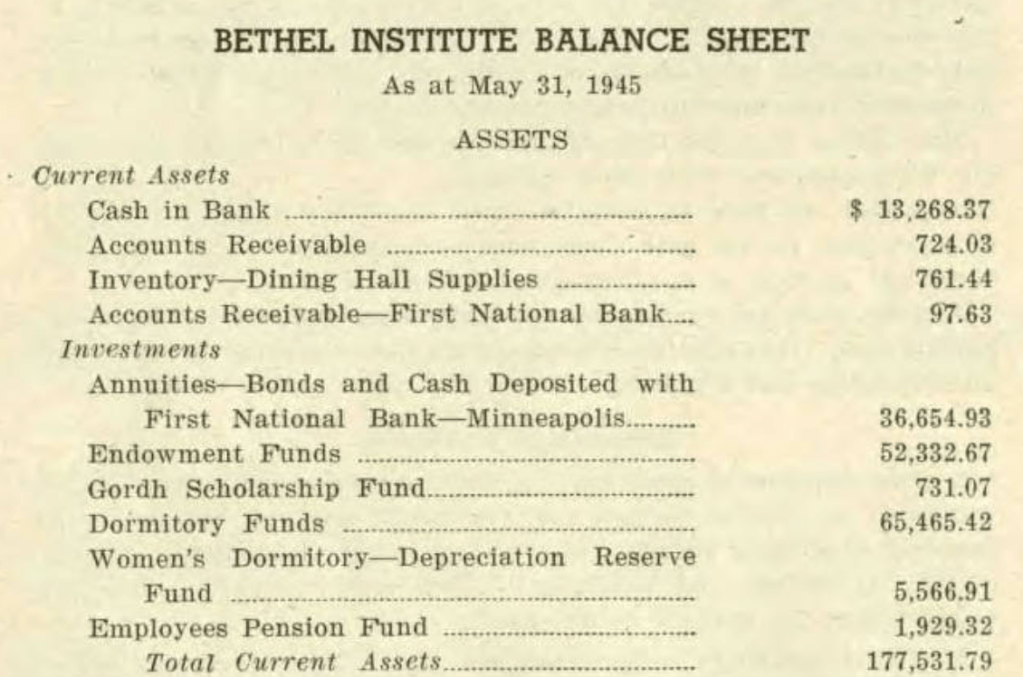

As World War II ended in Europe, Bethel Institute completed its financial report to its denomination, the (no longer Swedish) Baptist General Conference. For the first time, Bethel’s balance sheet included an “Employees Pension Fund” — all $1,929.32 of it.

The idea of that benefit wasn’t new. The 1938 report alluded to former Seminary dean Arvid Gordh reaching “the pension age,” and during the war the denomination had started to pay more attention to making retirement provision for ministers and missionaries. But as Bethel grew in the postwar years, its ability to recruit and retain qualified faculty became more important. By 1958 the pension fund was over $125,000 — roughly equivalent to $1.4 million when adjusted for inflation.

1958 was the year that Esther Sabel taught her last Bible class at Bethel. (“Seems funny not to have Miss Sabel there,” wrote pioneering female pastor Ethel Ruff, “but ‘the old order changeth‘ as we know.”) But because the pension plan had arrived relatively late in a thirty-four year career during which her salary was reportedly lower than that of male colleagues, she faced a precarious financial situation in retirement. Just how precarious — and how much she and other early female faculty had sacrificed to teach at Bethel — becomes clear from a poignant set of letters found in the archived papers of Carl H. Lundquist.

Though his presidency at Bethel only overlapped with the last four years of Sabel’s tenure, Lundquist knew her from his own time as a student in the Junior College and Seminary. Prior to returning to his alma mater, Lundquist had also pastored a Baptist church in Chicago, the home town to which Sabel moved back as a retiree. The two exchanged several notes through her first decades in retirement.

In 1965 Lundquist quietly reached out to Rev. Gordon H. Anderson, executive secretary of the BGC’s Board of Home Missions, to ask if something could be done to supplement Sabel’s quarterly pension payment of $137.16 — just $460 a month in 2025 terms. While the Board of Education had no extra resources available to assist “worthy individuals like herself who have given their entire lifetime to the work of our Conference but who do not have adequate retirement programs,” Lundquist wondered if a benevolence fund set up for BGC missionaries could spare a $300 gift to Sabel, perhaps underwritten by a special appeal at her home church in Chicago, Salem Baptist. Before the end of the year, Anderson had arranged to offer a $20 monthly supplement — which Sabel politely but firmly declined.

In a letter to Anderson written just before Christmas 1965, Sabel acknowledged that two hospital stays, the rising cost of living, the looming expense of moving into a retirement home, and learning that Bethel was planning to raise the pension for current but not retired faculty had left her “a bit panicky.” She admitted to “feeling sorry for myself,” enough to have written a letter that seems to have prompted Lundquist’s request for a one-time gift. But she felt “ashamed immediately” and wrote a second letter to apologize. “The Lord has been very, very good to me, and I have not suffered,” she insisted to Anderson. “If this money were from school funds, I should feel that in a sense I had earned it in the very lean years at Bethel. But I simply could not take it from a fund intended for people who have less than I have; and I am sure there are still a number of older pastors and wives who are really in need of help. Therefore, I am returning the check. Please do not think me ungrateful; I am not.”

There things sat for four years, until Lundquist received a renewed appeal from a Dr. Charles R. Berg. Like most early women on the Bethel faculty, Sabel had never married, but her niece Alice was married to Berg, a dentist in Chicago. Writing in May 1969, after another surgery forced Sabel to look for an affordable retirement home, Berg’s outrage on behalf of his wife’s aunt was palpable:

After thirty-four years of labor as the Lord’s handmaid on the faculty, Esther Sabel receives the “magnificent” sum of Forty-five dollars per month as her retirement income… Furthermore, for most of those thirty-four years, Miss Sabel worked for less than $100.00 per month. In fact, for two of the “leanest” years, she, along with some other faculty members, voluntarily took a ten percent cut in salary. Then too, she assisted many students sacrificially by contributing in part to their financial needs to the neglect of her own. All of this precluded the building up of any substantial savings for retirement. Her life, in fact, has remained a living endowment that benefited Bethel far beyond the remuneration received in return.

“It seems obvious to me,” Berg concluded, “that Bethel has some responsibility and obligation to make provision for these phenomena” — starting with a review of the retirement benefit that should increase Sabel’s pension by “several orders of magnitude at the very least” and peg it to the cost of living.

Still eager to help, Lundquist continued to correspond with Berg, who reported that August that Fridhem, a BGC retirement community in Chicago, had accepted Sabel for the fall. Its admission committee “took into consideration her service to the Lord on Bethel’s campus,” Fridhem administrator Gilmore H. Lawrence told Lundquist, and accepted her on a lifetime contract as part of the organization’s mission to serve “our Conference people when the need requires our help.” After turning over her Bethel pension and her $136 monthly Social Security check, Sabel was left with $50 each month for personal use. Berg was worried that this left her unable to afford her annual trip to Florida, where her two brothers lived, and asked Lundquist to arrange a supplement via some mechanism that she wouldn’t be as likely to refuse.

The details of the story peter out at this point, but I can add two items. First, Sabel thanked Lundquist in October 1970 “for the note indicating an increase in the pension.” Second, she lived at Fridhem — later renamed Fairview and relocated to the suburb of Downers Grove — as long as she had taught at Bethel, dying there in November 1993 at the age of 100.

“She was thoroughly and completely dedicated to learning,” Alice Berg told the Chicago Tribune when her aunt passed away. But “when others got raises, she didn’t because she was a woman and single and supposedly didn’t ‘need it’… That’s the way things were.”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.