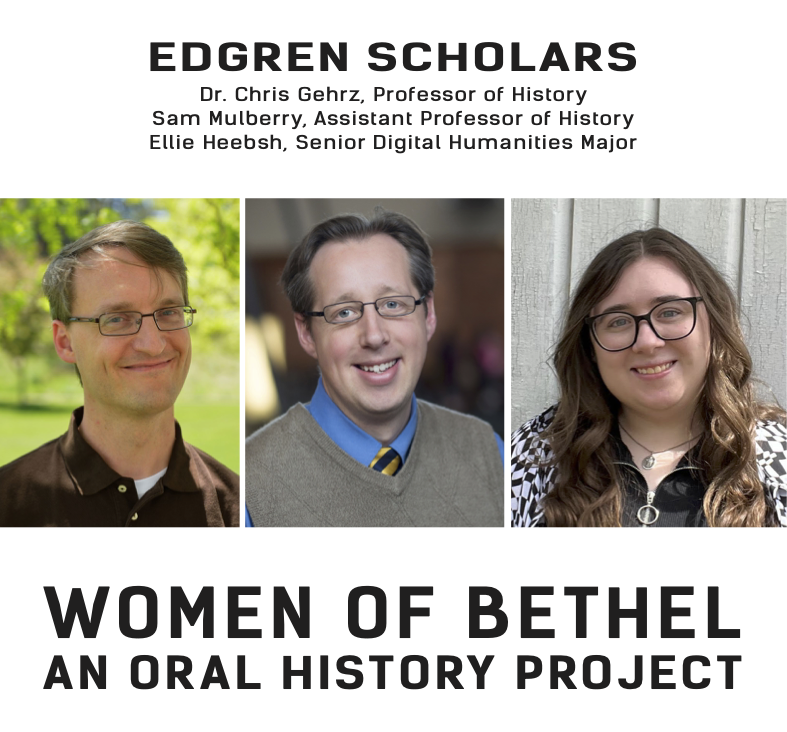

You may have noticed that not much has happened at this blog in recent weeks. While I expect that to change in April-May, as more time opens up in my schedule to devote to new archival research, March was quiet here because I was busy with two other projects related to this one. First, I was editing and publishing daily entries in our new Bethel Women’s History Month Devotional at Substack, which has had about 15,000 total views heading into its last weekend. Second, I was wrapping up the Women of Bethel oral history project that Ellie Heebsh, Sam Mulberry, and I started last June.

We presented our project at the Bethel Library on Tuesday, March 18th. We had a terrific turnout for that event, which included a seven-minute sample of interviews (embedded farther down this page) and remarks from four of the interviewees themselves. If you missed it, the video is available on YouTube (embedded above) and through the Spark repository.

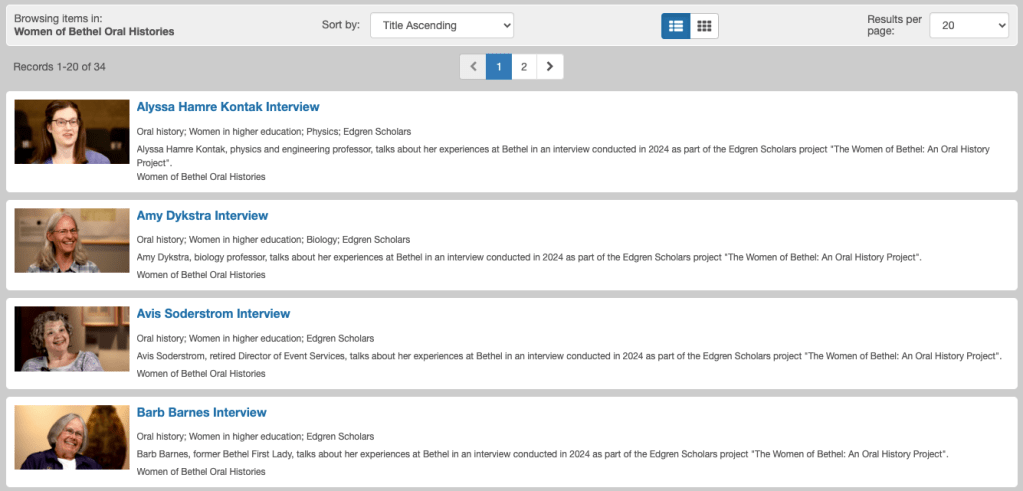

One day before, our oral history page went up at the Bethel Digital Library, where you can watch lightly edited videos of all thirty-four interviews. I’ve added that link to this site as a tab at the top of the screen, and I’m sure I’ll both quote those interviews and embed clips from them as I write my final women’s history narrative over the summer. Most of those interviews were filmed in person on the Bethel campus, but we did a couple via Zoom — including the one below with Tricia Brownlee, the Bethel volleyball and softball coach, physical education professor, and pioneering academic dean who retired in 2001 and now lives back in Louisiana.

As we came to the end of that project, I shared some reflections at my own Substack newsletter. Here’s part of what I wrote…

Most of all, it’s always gratifying to see an idea take shape and bear fruit — an experience that invariably leaves me feeling grateful to a long list of people.

I’ve inherited from my dad the kind of imagination that’s always dreaming up future projects, and from my mom the detail-oriented pragmatism to turn vision into reality. But none of that can happen without the help of other people: in this case, my co-researchers Ellie and Sam; the women we interviewed; Bethel’s archivist (Rebekah Bain) and digital librarian (Kari Jagusch); the previous Bethel historians on whose foundational work we built; the committee that recommended approval of our project; and the administrators who ensure funding for such scholarship.

…History is a multifaceted activity, involving many different ways of engaging with the past. But none of the other verbs we tend to associate with our discipline — study, examine, analyze, discover, reconstruct, communicate — would be possible without this one: preserve.

History is a form of storytelling bounded by evidence, but the sources we rely on are partial and fragmentary, typically growing more so with the passage of time. Historical sources often fall victim to neglect, decay, and forgetting, sometimes to concealment, distortion, and erasure. Worse yet, many memories of the past are never recorded; many voices are silenced by death, never to speak again.

So oral history offers us a way to preserve otherwise elusive first-hand accounts of what happened and what it felt like. Often, it’s our best way to hold onto the memories of those who, one way or another, were marginalized in their own time.

Doing that kind of history feels unlike any other. First, it carries a unique weight: the honor of being entrusted with stories that are meaningful to those telling them, some of whom might not be around much longer to share their memories; the lament that not all such stories can be preserved, either because oral historians only have so much time and energy or because we missed our chance to interview someone; the fear of getting wrong work that feels something like sacred.

For in order to do the work of preservation, historians need to suspend their deeply ingrained instinct to make meaning of evidence. In the moment of each interview, my job was not to analyze or interpret a source, but simply to listen to that person. To give her space to speak her piece, intervening only when it could help prompt recollection and reflection. To make her feel safe enough to speak as candidly as she could.

“Safe” because these stories are not always pleasant to recall. Indeed, one of our stock questions was both straightforward and complicated: Was it ever difficult to be a woman at Bethel? So while many of our interviewees told us how much they enjoyed the opportunity to think back over their time at Bethel, such questions inevitably dredged up painful memories.

For my part, I always start such institutional histories nervous that I might serve Bethel less gladly as I learn its past more fully. After all, such work can never be entirely celebratory or inspiring. As one of the humanities, history is ultimately a study of humans: creatures who are both wondrous and warped; saints and sinners simultaneously. Worse yet, institutional history studies such individuals who work for organizations where instincts for self-preservation don’t always conduce to treating people well or engaging in honest self-examination.

I’ve been a Bethel faculty member long enough see many of the university’s flaws for myself, but talking to women whose experiences often stretched back decades before I arrived was bound to complicate my lingering idealism about this place. And we did hear stories that are troubling: of women being harassed and trivialized, talked over and put in their place, questioned for simply doing their jobs.

But more often, we heard stories of women who relished their time at Bethel, who found their divine calling and employed their God-given gifts here, who were empowered by the men they worked with. Most clearly, we heard how women at Bethel had been supported, encouraged, and mentored by other women at Bethel. Indeed, that theme came through so clearly that Ellie (who’s majoring in both History and Digital Humanities) created a data visualization of the network that emerged from our interview transcripts, while Sam and I edited together the video below to illustrate those themes of intertwining stories of mutual support.

That clip closed with the woman mentioned most often by other interviewees: Deb Harless, a Bethel alumna who came back to her alma mater to teach psychology, serve as college dean, and conclude her career as Bethel’s first woman provost. As a student, Bethel had been “a really freeing place” for Deb, enabling her to ask questions and to discern callings that hadn’t seemed open to exploration. As a professor and administrator, she got to enable similar experiences for other young women — but also got to see more clearly the struggles and contradictions of an imperfect institution. How she summed up her long experience as a woman at Bethel articulates my chief takeaway from listening to her and thirty-three other women from Bethel:

I realize, I really do love Bethel, and sometimes I can make it sound too perfect, and there were challenges, for sure. But being a woman student, being a woman faculty member, being a woman administrator… overall, I was treated well. This is a place full of people committed in their faith and to living that faith. And when we fail or disappoint each other or treat each other badly, generally, we try to do better. So overall, Bethel was a really good place for me.

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.