As the 1970s began, Elaine Peterson left the western Wisconsin farm where she’d grown up and came to St. Paul, Minnesota to study for her career. She didn’t head for the University of Minnesota’s agricultural campus, nor any of the small religious colleges lining Snelling Avenue. Not even Bethel College, though two of her younger sisters who would later go there.

No, my mom went to the Arthur Ancker School of Nursing, a three-year program within St. Paul-Ramsey Hospital (now Regions Hospital) that trained registered nurses. By 1973 she had graduated and married my dad, then put her nursing career on hold when I came along two years later. By 1976, the Ancker School of Nursing had graduated its last students, as it fell victim to a trend that had accelerated since the Sixties: expecting R.N.’s to earn the broader education provided by a college degree.

Hospital-based nursing education in the United States dates back to 1873, when diploma programs began in New York, New Haven, and Boston. The number of those programs peaked at nearly 1,300 nationwide in the 1960s, but by then advocates of baccalaureate nursing education were more successfully arguing that increasingly complex health care systems in a fast-changing society required a different educational model. According to a recent article in the Journal of Christian Nursing, over 94,000 of those who took the R.N. licensure exam in 2021 held a bachelor’s degree; only about 2,000 had completed a diploma program.

The Ancker School wasn’t the only Twin Cities hospital program to struggle as that transition in nursing education proceeded. Leaders of Mounds-Midway School of Nursing had first proposed a merger with Bethel College after World War II, then again after it detached from Hamline University in 1960. Pressed by the state nursing board in the early Seventies, Mounds-Midway explored mergers with several colleges, including Bethel — which set up an advisory committee to study that option in 1974.

It was a logical match. Both institutions had originated in Swedish Baptist immigrant communities, with the nursing school starting within the Mounds Park Sanitarium — founded by members of St. Paul’s Payne Avenue Baptist Church in 1905, the same year that Bethel Academy opened its doors at Elim Baptist in northeast Minneapolis. “We would be preparing these nurses to be ministers of Christ in their field,” math professor and 1974-75 committee chair Phil Carlson told The Clarion, which later reported that Mounds-Midway’s director “would prefer a relationship with Bethel in order to preserve the spiritual distinctives it now has in common with Bethel.”

In spring 1975, Bethel’s board of regents agreed to move toward a program launch the following year. But it wouldn’t be until early in the next decade that Nursing finally came to Bethel, with the first graduates completing their degrees in the spring of 1984.

What held things up? I haven’t had a chance to dive into archival records related to this transition, so know that this post is just a first draft of a history that I’ll continue to flesh out. (And I’d certainly welcome comments from those present at the creation!) But it’s clear even at a first glance that there were three early problems with or objections to starting a nursing program within Bethel College.

First, the original 1974-75 advisory committee estimated that launching a nursing program would cost the economically strapped college $134,000 ($800,000 in 2024 terms), since Bethel would need to hire a department chair and nine other professors, plus additional instructors to teach science prerequisites. Even with Mounds-Midway donating equipment and dozens of new students bringing in additional tuition, a nursing major would require an annual budget subsidy of $80,000 (nearly half a million dollars, adjusted for inflation) at a time when students already complained about tuition increases and Bethel was struggling to build out its new campus in Arden Hills.

The intended 1976 start date came and went. By that point, The Clarion reported that the budget subsidy was up to $100,000, which Bethel president Carl Lundquist hoped could be funded by the Baptist Hospital Fund. In the end, it wasn’t until college dean George Brushaber (soon to succeed Lundquist) convened a new ad hoc committee in spring 1979 that final plans were made. After receiving approval from the college faculty and board of regents that May and September, respectively, Bethel prepared to build out additional classrooms, labs, offices, and dorms to accommodate up to 270 Nursing majors.

The administration also started recruiting nurse educators. In January 1981, The Clarion ran a front page profile of Eleanor Edman, the founding chair of the Nursing Department. By the following year, its faculty included fixtures like Nancy Larson Olen, Beth Peterson, and Sandra Peterson, each of whom would spend twenty years or longer at Bethel.

As early as 1975, Bethel professors in fields like sociology and philosophy had gone to Mounds-Midway to teach general education courses. But a Clarion article that fall had named a second obstacle to finalizing the merger: “the compatibility of a nursing program within a liberal arts framework.”

Some broader context here… The Business major was just getting off the ground, and Bethel had long had teacher training programs and a pre-seminary track. But it has been striking to read so many Bethel folk in the Seventies and Eighties — students, administrators, and faculty, including those in programs like Business and Computer Science — insist that Bethel was a liberal arts college, committed to giving young Christians a broad education in the arts, humanities, and sciences rather than preparing narrowly focused professionals.

“There was an opposition to the fact that it was a completely different kind of program,” Edman acknowledged when we interviewed her this past summer, since other faculty were already asking, “Is nursing really a liberal arts program, or is that just a practice program?” Beth Peterson agreed, noting the challenges inherent to adding a major with the size and complexity of Nursing: “I think there was a very strong belief that [Bethel] was a liberal arts institution, period,” yet “there had to be some wiggle room in curriculum because there were certain topics that we simply had to include in our curriculum.”

Perhaps with an eye to such concerns, it’s noteworthy that the 1979 committee that made final plans for Nursing included faculty from Anthropology, Chemistry, English, and History, as well as Education professor Tom Johnson, who first reached out to Edman. As department chair, she made a point of encouraging Nursing professors to get out of their department and get to know colleagues from a variety of disciplines. “For the first year that we were here we were basically developing curriculum,” recalled Peterson, “but at lunchtime — I don’t want to say [Eleanor] would drag us down because we went willingly — but it was like time to go to the faculty lounge… to eat lunch with other faculty and talk about whatever faculty talk about.”

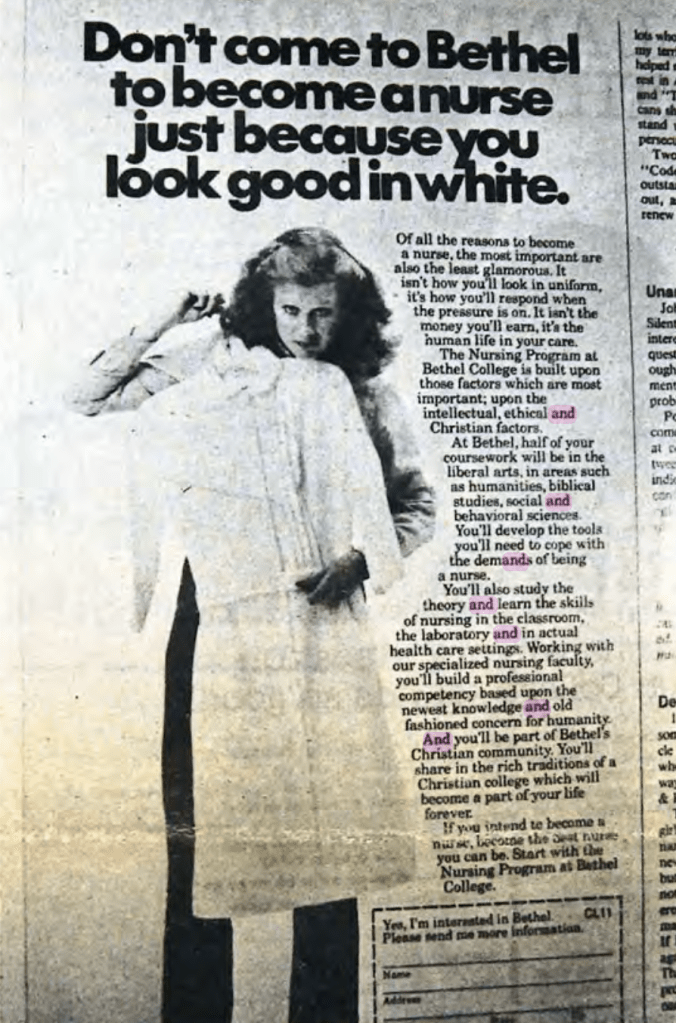

In a 1982 ad for the program that I’ll revisit at the end of today’s post, the text emphasizes that Nursing majors’ “coursework will be in the liberal arts,” where studies in humanities, social and behavioral sciences, and biblical studies would help students “develop the tools [they’ll] need to cope with the demands of being a nurse” — even as they “build a professional competency based upon the newest knowledge and old fashioned concern for humanity.”

But that ad (pictured below) also reawakened the third issue raised early in the debate over Nursing at Bethel — the one that’s most obviously germane to my larger project.

During the spring 1975 elections for student body president and vice president, The Clarion asked candidates what they thought about the possibility of a Bethel nursing program. In a year when women made up 54% of Bethel’s undergraduate enrollment, the two men who ended up winning the election worried that recruiting Nursing majors would make it “virtually impossible to maintain the balance between male and female students which we would like to see.” (That November a Clarion column on dating fretted that “Gals [sic] hope goes as sex gap grows.”)

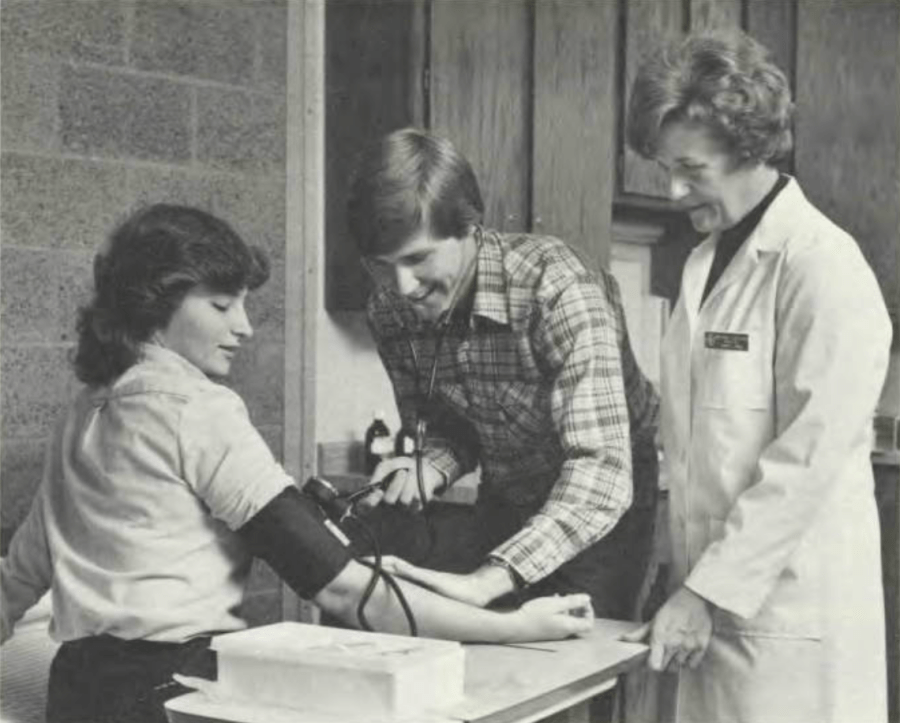

As the History Center documentary embedded above notes, Mounds-Midway didn’t enroll its first male students until 1972, and they continued to make up a small percentage of the school’s student body. “If Bethel keeps up with the national average, about ten percent of the nursing students will be men,” reported student journalist Lori Rydstrom in October 1979, adding that George “Brushaber would like to encourage men to consider the program seriously because of the excellent career opportunities.”

Men did enroll in Bethel’s Nursing program from the start. Here again is the photo of Edman and students Donna Fray and Jon Erickson that I used in an earlier post noting that the launch of the Nursing program pushed the women’s share of the Bethel College faculty to 25% by the mid-Eighties.

But a front-page Clarion story in November 1982 fretted that the program recruitment ad above fed sexist stereotypes about nurses. “It is more honest for us to put a female nurse in the ad because 95 per cent of the nursing students are female,” responded Florence Johnson, Bethel’s publications director. And the actual text of the ad emphasized that “the most important reasons [to become a nurse] are the least glamorous. It isn’t how you’ll look in uniform, it’s how you’ll respond when the pressure is on. It isn’t the money you’ll earn, it’s the human life in your care.”

But a letter to the editor the following week described the ad as just “a small example” of how “sexism is rampant” at a college with growing numbers of female students and faculty. Cindy Oberg said she’d love to see Bethel advertise women studying systematic theology, “but I won’t hold my breath.”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Today I’d especially welcome recollections from faculty and alumni who were firsthand observers of the founding of the Nursing program in the Eighties — or the debate over it in the Seventies. Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.