Just a short post to end a week in which Donald Trump became the first former U.S. president since Grover Cleveland to win reelection to a second, non-consecutive term. In the process, Kamala Harris fell short of becoming the first woman to be elected president of the United States.

While Hillary Clinton had made the breaking of “the highest, hardest glass ceiling” in American public life a centerpiece of her 2008 and 2016 presidential campaigns, Harris (the nation’s first female vice president) rarely emphasized her chance to set that precedent in 2024. Asked about it by CNN’s Dana Bash, Harris insisted that she was “running because I believe that I am the best person to do this job at this moment for all Americans, regardless of race and gender.” In a post-election story wondering if the country will ever send a woman to the Oval Office, the Associated Press reported that the potential of Harris making that history was the most important factor for only one in ten voters.

None of this is central to my Women of Bethel project. But looking back at women who have run for high public office does offer a potential window into how students and others at Bethel have debated the role of women in society.

Searching the online archives of The Clarion for coverage of the 2016 election, it’s striking how rarely it discussed the most historic aspect of Hillary Clinton’s candidacy. But after she suffered an unexpected defeat at the hands of Trump, op-ed writers did debate whether gender had played a role. “The majority of those who celebrated Nov. 9 did not celebrate because they believed racism, misogyny or white supremacy had won,” wrote Abby Peterson a month after that election. “But people who mourned and grieved Nov. 9… wept because more than 60 million people voted for a man who normalized and vindicated racism, misogyny and white supremacy.” A year later, conservative contributor Sam Krueger insisted that “Hillary didn’t lose because Americans are sexist or xenophobic… She lost because Trump seemed like he was the only candidate with something to offer. She lost because Republicans promised to put America first.”

Eight years earlier, the student newspaper had mentioned Clinton only in passing before she lost the Democratic nomination to Barack Obama. Reviewing the vice presidential debate later in 2008, Clarion reporter Nelly Patterson complained that Alaska governor Sarah Palin (the first Republican woman nominated for that office) smiled too much, winked and blew kisses to the audience, and often “had the ‘mom’ look, which she repeatedly used on [Democratic VP nominee Joe] Biden.”

As far as I can tell, The Clarion said nothing at all about the pioneering presidential candidacies of Democratic congresswomen Shirley Chisholm (1972) and Patricia Schroeder (1988). But its limited coverage of the 1984 election did make much of Walter Mondale choosing a woman as his running mate.

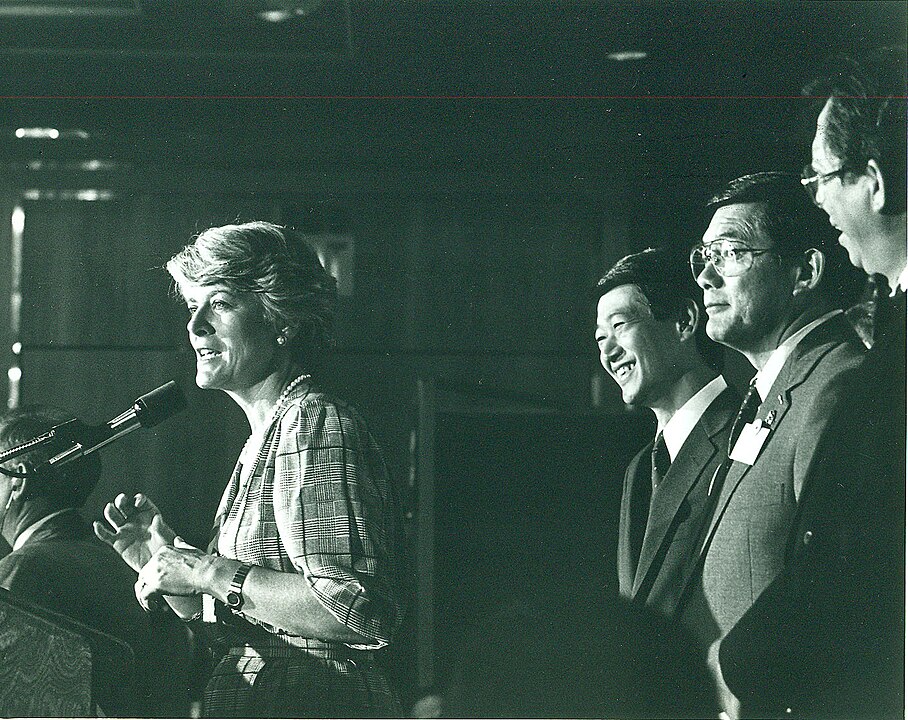

In a pre-election issue that also reported on political science student Connie Hope interning for the state Independent-Republican party, a two-page interview with Mondale and Reagan supporters on campus made multiple references to New York congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro’s unprecedented nomination. History professor Jim Johnson backed the Democratic ticket not only because it continued to support the Equal Rights Amendment but (in the reporter’s paraphrase) “for being willing to run a woman for an office that is one heart-beat away from the presidency.” Pro-Mondale/Ferraro senior Carolyn McAnally was “amazed I’m living in a time that’s actually happening.” Pro-Reagan/Bush junior Brian Stevens opposed Mondale and Ferraro, but liked “the idea of women in politics,” pointing to Margaret Thatcher’s work as prime minister of Great Britain. Of the four interviewees for that story, only dean of women Marilyn Starr made no allusion to Ferraro, explaining her habit of voting Republican in terms of her belief “in free enterprise, and in less government involvement in the lives of individuals.”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.