Perhaps the hardest thing to do as a Bethel historian is to recover the experience of the university’s largest constituency: its students.

That’s partly because of the sheer size and diversity of that group. Across its whole history, over 50,000 people have attended Bethel; in every year covered by this project (1972 and on), Bethel was home to no fewer than 1,300 students. How can any historian possibly account for even one moment shared by so many people?

(I’m already starting to think that I’ll need to keep my focus on the traditional day college and seminary, leaving the graduate school and adult programs to later scholars, if I’m going to have any hope of completing this project on time.)

Of course, a smaller version of the same problem applies to the faculty, staff, and administrators on campus. But those groups at least tend to leave behind much more historical evidence. They’re more likely to publish their ideas in books, journals, and magazines, to participate in processes (e.g., the work of committees and task forces) whose records are preserved in institutional archives, and to be interviewed years later by people like me during oral history projects like the one I helped direct this past summer.

Several of the employees we talked to at length were also former students; I’m glad that their memories of their undergraduate or seminary years at Bethel are now part of the historical record. This fall I’ve conducted a handful of email interviews with selected alumni, to help fill in holes related to central themes in my project (e.g., women in ministry, women in sports).

But if we want to get a snapshot of what the wider student population believed and how it behaved at any point in our narrative, our most promising resources are the student publications that have been added to Bethel’s Digital Library. I’ve already touched on yearbooks in previous posts. But this week I’ve spent much of my time reading through back issues of an even older Bethel student publication: The Clarion.

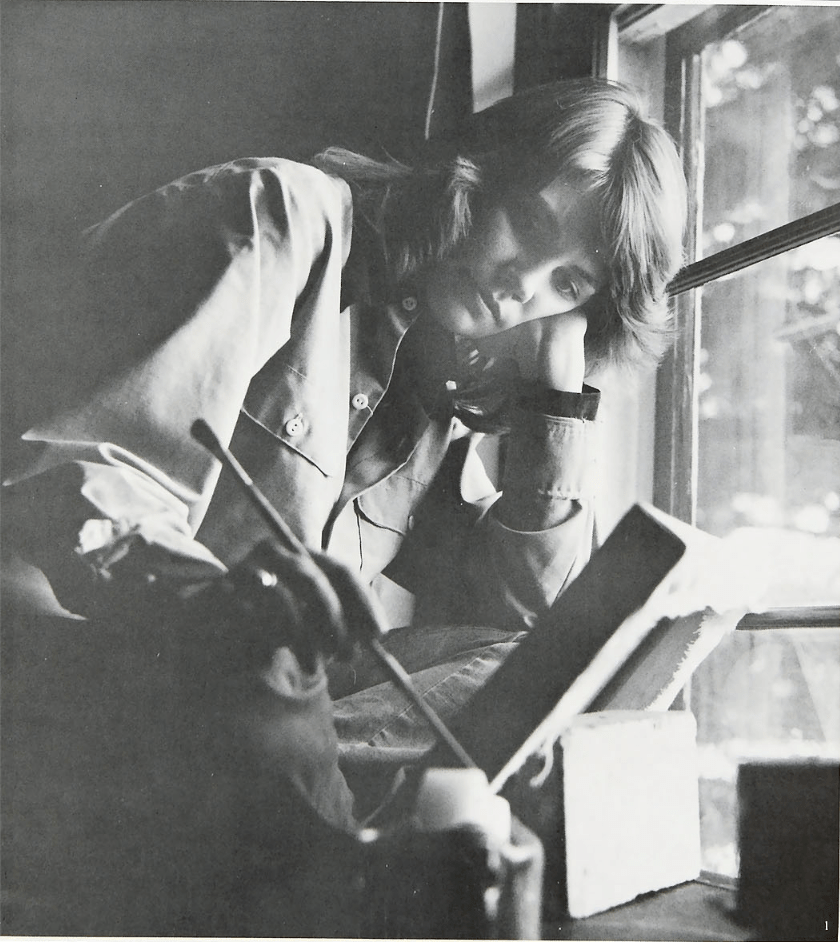

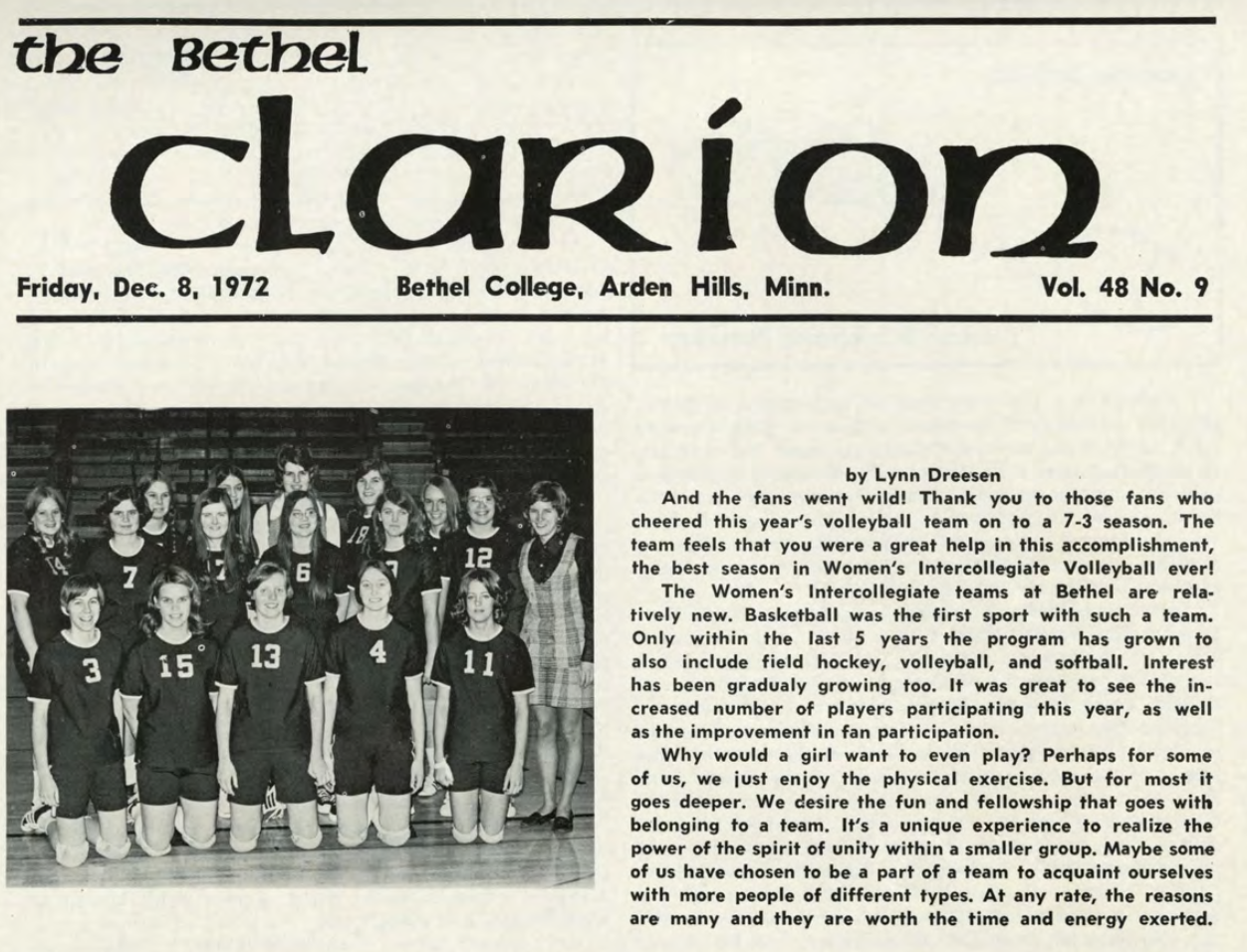

For the sake of time, I won’t go all the way back to the student newspaper’s origin in 1921. But even starting with the nine issues digitized from the year the College relocated to Arden Hills, you can get some sense of the potential — and problems — with student newspapers as a type of historical evidence. For example, the 1972-73 run of The Clarion debated dating culture on campus after Nik Dag, the fall event to which Bethel women traditionally invited men (“Thank goodness the sex roles are exchanged only once a year,” wrote one anonymous female contributor) and profiled the “house mother” for one of the first dorms to have both male and female residents. Amid otherwise sporadic coverage of women’s sports in the year of Title IX, the cover of the December 8, 1972 issue was dedicated to the women’s volleyball team, with student-athlete Lynn Dreesen answering the question, “Why would a girl even want to play?”

As with other primary sources, silences sometimes cry out for attention. In the 1972-73 Clarion issues held in the Digital Library, not only Title IX but the Equal Rights Amendment and the Supreme Court’s Roe v Wade decision go completely unmentioned. Perhaps the relevant articles just haven’t been preserved; abortion, after all, is discussed in Clarion issues from the year before and after. Or we might assume that the 1972-73 editors were simply less inclined to address political or cultural controversies, or that the administration didn’t let them…

Except that The Clarion that year published an “Issues in Focus” column in which students Chuck Jackson and Dan Blomquist rather bluntly discussed everything from the Nixon-McGovern race to larger debates over foreign policy, race, and poverty. If we’re not seeing student commentary on the ERA or Roe, it may simply confirm their complaint (in the December 15, 1972 issue) that

apathy is alive and well at Bethel College… The social and intellectual sterility at Bethel is sometimes appalling. Last May when University of Minnesota students were protesting the Vietnam War, Bethel students were having a water fight…. At another time in the school year, Nik Dag controls the minds of a major segment of the Bethel population, to the exclusion of any concern for events like an election or a peace settlement.

Perhaps to stir later Bethel students out of a similar apathy, the 1984-85 Clarion ran “Windows Without Shades,” an opinion series “devoted to women’s issues.” While they affect everyone, editorial assistant Julie Bach continued, these

issues rise out of a growing women’s consciousness, a new vision, that is making us look at things we’ve never looked at before. This column will do the same….

Most significantly, [the series] will affect the way we look at our world. It will offer alternate patterns of structuring institutions, relating to one another, even dating. If we are going to deal with these institutions, live with each other, and form families, we are going to have to understand this new way of looking at the world. We are going to have to take the shades off our windows and gaze with understanding over a new landscape.

Most contributors to the series were older. My own project is effectively an extension of what history professor Jim Johnson wrote at the end of his column: “Women’s history is alive and well, and our task at Bethel College is to join in and be part of such a movement, rather than be left out and deny the validity of historical reality.” Journalism instructor Alvera Mickelsen looked to church history to complicate “‘the traditional view’ of women’s roles in home and church,” and her English department colleague Jeannine Bohlmeyer explained why inclusive language was a matter of justice. Lyn Lawyer (wife of political science professor John Lawyer) reflected on her experience as a deacon in the Episcopal Church, and Marilyn Starr, Bethel’s dean of women, shared the challenges facing single women in the church.

But it’s Bach and the other two student contributors to the series who stand out for wrestling with the larger issues of gender in American society. Copy editor Elizabeth Tederman celebrated women coming to realize that there was more to value than “the world of male experience.” Inspired by the work of Minnesota playwright Pam Carter Joern, Tederman described the emergence of a “sisterhood” whose members would confirm for each other “that female experiences are valid” and assure one another “that I do not have to become a pseudo-male to be a productive member of society.”

Likewise, junior Shari Erickson argued that evangelical Christians shouldn’t equate feminism with “men-hating, bra-burning and pushiness,” since it is actually “the essence of the gospel, ‘to love others as we love ourselves.'” Pointing to his interactions with women like the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4) and Mary and Martha (Luke 8), Erickson argued for a feministic reading of Jesus himself:

Jesus restores dignity to women. He brings powerful signs of the new status of women in the kingdom of God. He breaks the social rules to make women human. He loves all humans, disregarding their gender. He truly makes all people equal before God. This is the Jesus whom Christians claim to follow, the example after which we model our behavior. Jesus loved women so much that He could no longer allow social rules to hurt them and make them feel inferior. We can argue over Paul’s writings for a long time, and we will still come to different conclusions. Is it not most important that we try to live and act like Christ, who is God himself? Let us love one another as Christ has loved us. Feminism is not a dirty word: it is a word of loving other humans.

It’s unlikely that the “Windows Without Shades” series reflected anything like majority opinion in the mid-Eighties student body. “Many people may feel that these issues are a waste of time, or overworked, or unimportant,” acknowledged Bach in her introduction to the series. But writing the week after an election in which Geraldine Ferraro stood as the first woman nominated by a major party for the vice presidency, Bach insisted that “these people have already been affected, whether they are a part of this growing consciousness or not. They can no longer live in the world and be oblivious to these issues.”

I’ll be curious to see how those issues recur in the pages of The Clarion and other sources as I continue my research into the women of Bethel.

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.

Read this with great curiosity! I would say with regard to the Clarion silence in 72-73 publications, I’d bet money on it being an edict from administration. My senior year was 71-72, and we were really pushing hard for change. One of my sisters graduated from Luther in 1968, and at one of their reunions President Farwell was asked what were his most difficult years. He replied without hesitation 1968-1972! Luther was transformed in those four years and most of it was student-led. Admin was basically punting and trying to figure out the new realities.

Tame by today’s standards but unheard of at the ELCA colleges up to that point. Vietnam and environmentalism and “Womens Lib.” And Gay Rights. All sort of exploded at the same time. No wonder college administrators were circling the wagons. Anyway, no need to reply. Save your time and energy—this is important work!

Marilyn

P .S. The book I want to write is about the PE majors of my time at Luther. So Title 9 comes along in 1972. There of course were women who saw themselves as athletes. (There have always been female athletes!! ) Most of the time they did sports without coaches and no uniforms. They’d go to the bookstore and buy themselves matching tee shirts because there were no uniforms. Then they graduate in 72 and go out to teach PE in high schools and they have to figure out how to coach. Not having been coached very much at all! 1972-73 was pivotal! But the speed of change was supersonic and it was very destabilizing.

Marilyn Fritz Shardlow marilynshardlow@gmail.com 651-341-2983 (cell)

LikeLike

Chris Gherz reached out to me since I was at Bethel from 1968-72 and played on women’s sports teams. I am a missionary kid from Japan and at Christian Academy in Japan, I played on tennis, volleyball, and basketball teams. When I got to Bethel, I joined every team that was offered to women. I didn’t realize that in U.S. high schools, girls didn’t play on interscholastic teams. I recently read an article in the spring 2020 issue of Minnesota History and read about two court cases in 71-72 in which the MN Civil Liberty Union challenged the boys’ only sports culture in MN on behalf of two women athletes: a tennis player and cross country runner. My small K-12 school in Japan was ahead of Title IX.

I agree with Marilyn that 1968-72 were tumultuous years, but I playing sports with other student athletes gave us a constructive outlet. By today’s standards, we weren’t great athletes but we improved our skills.

And Bethel pulled together a PE major so I took most of the required classes for a PE major and was well-prepared to teach PE and coach cheerleading, volleyball, basketball, and even one season of soccer at Okinawa Christian School International where my husband and I taught for 25+ years.

LikeLike