If you want to understand how evangelical Christians debated the roles of women and men as the Seventies turned into the Eighties, you could do worse than to use Bethel and its denomination as a case study. Bethel faculty of that era founded organizations on both sides of the complementarian-egalitarian debate. While the Baptist General Conference avoided taking a stance for or against women’s ordination, that non-decision only sparked a fierce debate in the pages of its denominational magazine.

We’ll revisit this issue through other posts at this blog and then in a key section of our final Women of Bethel project, but let me go ahead and sketch the contours of the debate by drawing on a few sources from the Bethel Digital Library:

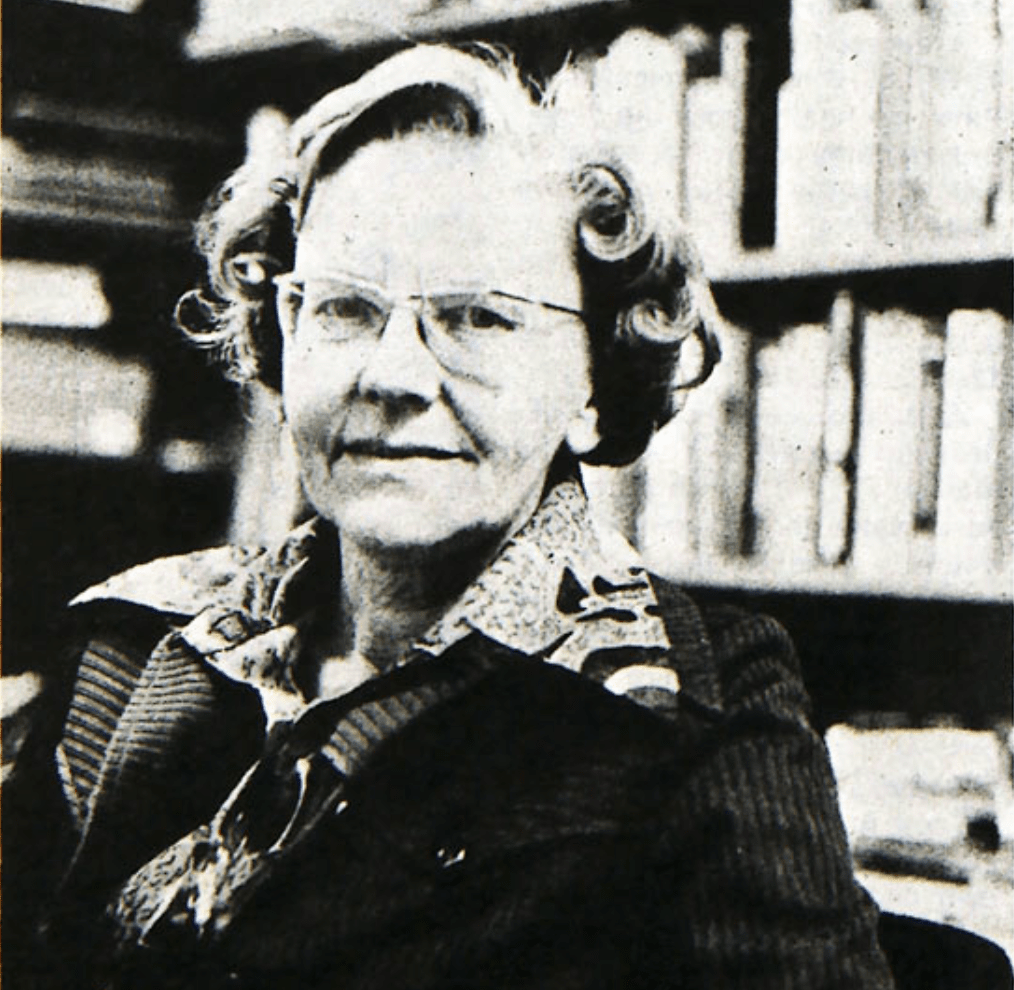

• A 1975 series on women’s roles by Lorraine Eitel, Bethel’s newest English professor, accounting for two of her many columns for The Standard, the BGC’s magazine.

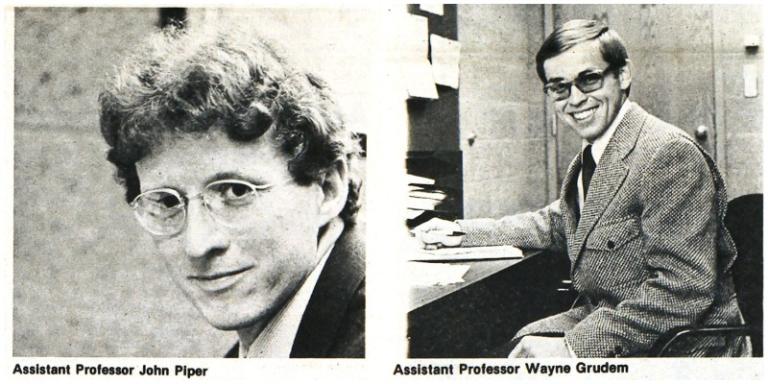

• A faculty forum in the December 9, 1977 issue of The Clarion, Bethel’s student newspaper, in which six Bible and Theology professors from the College and Seminary answered the question, “Should women be ordained pastors of churches?” Half said yes; half said no.

• The Standard‘s editorial in February 1980 (most likely written by editor Donald E. Anderson) defending the BGC governing board for taking a resolution on “The Role of Women in the Church” off the agenda of that summer’s annual meeting in Erie, Pennsylvania.

• A series of letters to the Standard editor in March-July 1980 in response to that editorial — most fiercely critical of the BGC’s decision.

So, which questions and arguments tended to come up most often in the Bethel/BGC version of the debate over women’s roles (particularly women’s ordination)?

Are women and men equal? Complementary?

“I see no account that says God created two races: people and women,” Lorraine Eitel began her series for The Standard. “Women are, after all, human beings. To the Christian especially this concept should ring true because our heritage, recorded in the Bible, is full of women acting as people, fulfilling God’s will. And we believe that God created both people and women ‘in His own image.'” In their basic desires and drives, women “want what you want. Nothing more—but nothing less.”

Eitel acknowledged biblical examples of women “who get their identities from their husbands, sons and brothers and are happy in that role,” but also noted women from Scripture who had been called to ministry, government, business, and poetry. “When diversity is not allowed,” she concluded, “when human beings are coerced to conform to only one role, denying their humanity, those human beings will either wither or rebel.”

When Wayne Grudem argued against women’s ordination two years later, the College’s newest theology professor was careful to tell The Clarion that “this difference in roles certainly does not mean that women are inferior to men,” any more than Jesus obeying his Father (Phi 2:8) left him anything less than “equally divine and equally important in every way.” But having prescribed gender roles that excluded women from certain work — in this case, public preaching to and teaching of men or having ruling authority in churches — should “not be seen as a burden to tolerate (1 Jn. 5:3) but, like all of God’s law for us, will be seen by men and women alike as a great joy and blessing and delight.”

John Piper’s response to the student paper was much shorter, but also made clearer that his opposition to women’s ordination was rooted in a larger view of gender complementarity. “My opinion,” the biblical scholar concluded, “is that Paul had a profound insight into the God-given distinctives of male and female. And I think his view which calls for male headship in the home and male authority in the church is a divinely inspired means of preserving the health of the church and the unique glory of man and woman.”

(Piper and Grudem, who left Bethel in 1980 and 1981, respectively, helped found the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood in 1987. Its founding document, the Danvers Statement, first affirms that “Adam and Eve were created in God’s image, equal before God as persons and distinct in their manhood and womanhood (Gen 1:26-27, 2:18).”)

Arthur Lewis, an Old Testament professor at Bethel College, agreed that men “have a priority in authority and leadership by creation” in the home, but not in the church, where he thought that “women will eventually recover leadership roles… and eventually we will recognize all their Spirit-given gifts.” Seminary professor Berkeley Mickelsen went much further, arguing that God’s original intent for Creation was “complete partnership, interchangeable roles in terms of ruling, subduing, and controlling the world.” What Piper and Grudem described as God-ordained differences in roles were, to Mickelsen, effects of humanity’s fall into sin, which built up “friction… between races, sexes and economic classes.” The Gospel, in turn, restored harmony in all human relationships: “In Christ the old things pass away such as the battles between the sexes, races, and slaves. We cannot glorify the fall and make that normative.”

(Mickelsen’s wife Alvera, a longtime journalism instructor who had attended Bethel Seminary before completing her education at Wheaton College and Northwestern University, helped found Christians for Biblical Equality in 1988.)

Are differing gender roles cultural or biblical?

“Cultural ideals—even false ones—die hard,” observed Eitel, describing the notion of woman as a “delicate, feminine, helpless, not-quite-human creature” bound to the domestic sphere as a relatively recent cultural construct, not a divinely ordained ideal. “Yet, for the Christian,” she continued her second women’s work column, “cultural mores should constantly be under scrutiny. Our touchstone for values and lifestyles is the Bible.” Against “the helpless status symbol” of modern culture, Eitel contrasted the “virtuous woman” of Proverbs 31, “a real worker” with “a profession beyond her home” who was “not afraid of showing her expertise in the business world.” (Maybe not coincidentally, this was the same year that Bethel piloted its Business major, a program that initially struggled to attract women students and faculty.)

Likewise, Donald Anderson’s 1980 Standard editorial on women’s ordination insisted that “sociological and cultural considerations” — such as “the assertiveness of women for leadership… in other professions” — “are not determinative. Conference Baptists in this matter, as in every other, should appeal first to the Word of God for enlightenment and direction.” But while Anderson found women playing important roles in the New Testament (e.g., “first witnesses of the resurrection of Christ”), they were “not ordained as bishops and elders and pastors to serve in churches. The issue is not subordination or inferiority; it is conformity to God’s revealed pattern.”

In the earlier Clarion forum, New Testament professor Robert Stein felt compelled to take the “unpopular position” of opposing women’s ordination because, like Martin Luther, his conscience was captive to God’s word: “If someone can show me from Scripture [that I am wrong], I shall gladly recant, but he must show me from Scripture and clear reason. ‘Here I stand! I can do no other. God have mercy on me.'”

Grudem put it even more firmly in his “Definitely not” response to the Clarion‘s question about women’s ordination: “The question here is whether we are going to obey the Bible or conform to the pressures of modern society.” While he allowed that other New Testament passages permitted women to teach children (1 Tim 5:14) and other women (Tit 2:4) and informally share doctrinal views with men (Acts 18:26), Grudem — like all other complementarians in these sources — placed particular emphasis on 1 Timothy 2:12 (“I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent” — RSV). He rejected the argument that “Paul’s injunction here applied only to his particular culture,” since the apostle appeals in vv 13-14 “to the situation of Adam and Eve before the Fall.”

We’ve already seen that Mickelsen disagreed with that interpretation of Creation and Fall, but he and Lewis also argued that their colleagues were reading far too much out of a single scripture in one epistle, a passage that they took as nothing more than Paul illustrating the problem of an overly aggressive or domineering partner. In his more lukewarm endorsement of women’s ordination, College Bible professor Walter Wessel likewise deemed it “precarious to base any doctine [sic] on one passage of Scripture.” He didn’t “want to over dogmatize where Scripture doesn’t over dogmatize.”

For their part, complementarians were unconvinced by egalitarians’ frequent invocations of Galatians 3:28 (“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus”). Stein warned against taking what he saw as the purely soteriological claim of “neither male nor female” as implying “that there are no distinctions between the role of men and women in the home and in the church….”

Anderson made a similar argument in 1980, yet writer after writer invoked Gal 3:28 in their heated responses to his editorial. (Others pushed back against Anderson’s hesitation to consider the Junia of Rom 16:7 a woman or an apostle.) That summer, for example, David W. Barkey of Galilee Baptist Church in Loveland, Ohio imagined Jesus telling a parable to religious leaders skeptical of women prophesying. “Just as My kingdom breaks down the distinctions of rich and poor, slave and free, black and white, it also breaks down the division between male and female,” concluded his Jesus, who then alluded to Joel 2:28, another popular verse among egalitarians: “Truly I say to you, the Spirit endows whom He will. It is the one Spirit who will indwell each of My ministers, male or female. Beware lest by opposing one of my servants on the basis of gender, that you oppose the Spirit of God.”

What about church history and personal experience?

While he ultimately concluded that God “has given the positions of leadership in the church to men,” Donald Anderson did acknowledge that “pastoral service by ordained women in the Baptist General Conference has been a quiet, almost unobserved phenomenon for decades.” (I wrote a bit about this in an earlier post on Adolf Olson’s centenary history of the Conference. I’m sure I’ll say more about women like Ethel Ruff before too long.) In his June 1980 response to that editorial, retired pastor Edwin Brandt recalled women who, like him, had graduated from Bethel Seminary and served BGC churches:

I must in all honesty state that they were eminently blessed of God as pastors, evangelists and administrators. They were fully accepted by church laymen, laywomen and youth. I cannot see how we can stand in their way by quoting a few Bible verses that on the surface seem to bolster our view. The interpretation of Scripture is solemn responsibility. We must not slip lightly over the rules of hermeneutics, nor can we disregard the facts of a pagan culture that had for too long enslaved women to serve male ends… I take my stand at the side of the women as they seek a right under God which we must not deny them

Pointing to the long-standing tradition of sending women as missionaries to other parts of the world, Arthur Lewis had asked in 1977, “Why can we not be open to the practice here in America?” Noting that opponents of women’s ordination had not sought “the recall of any of our women missionaries who have been active in the spread of the gospel abroad on the basis that they are violating God’s will as evidenced in Pauline writings,” letter-writer Robert L. Reed (also of St. Paul’s Central Baptist) asked fellow BGCers in July 1980, “are we, in our arrogance, willing to say that it is all right for white women to exercise authority over non-white men in underdeveloped countries, but not over white middle-class men in North America?”

None of that history would have persuaded Wayne Grudem. To his mind, making an argument on the basis of women identifying calls to ministry and manifesting gifts of preaching and teaching was “just a way of suggesting that God might require someone to disobey Scripture.” He acknowledged that “women pastors have been used and blessed by God in the past. But Scripture, not experience, must be our standard. If Scripture is our standard, then we must say that God has blessed women pastors in spite of their disobedience of 1 Tim. 2:12, and not because of it.”

Who ultimately makes the decision?

In any event, a 1979 BGC resolution deemed ordination “a necessary function of the local church” and left gender unaddressed. To this day, the matter of women’s ordination in what’s now called Converge is ultimately up to congregations, not individuals or the denomination.

BGC leaders likely feared the same backlash that Walter Wessel did. In his 1977 response to The Clarion, he wanted to “be careful not to force women upon congregations,” since he expected that “the Baptist General Conference will eventually accept women readily. But probably not in my lifetime.” His colleague Art Lewis agreed both that “we can not force the leadership by women on our society” and that the question of women’s ordination did indeed require a “local answer.” But Lewis also insisted that “every church should recognize the God-given talents of its women members. Ordination is not the church’s decision, but is the recognition by the church of God’s decision and God’s call whether to [ordain] a gifted man or woman.”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.