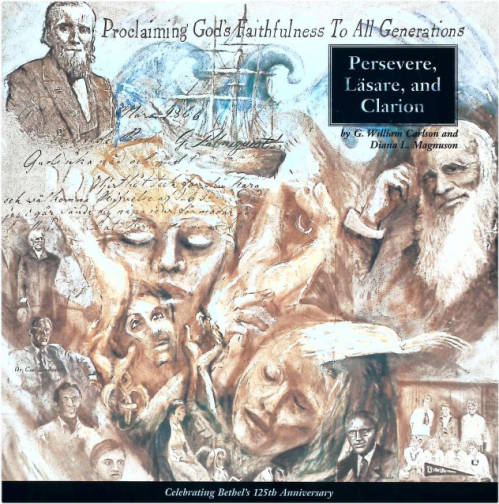

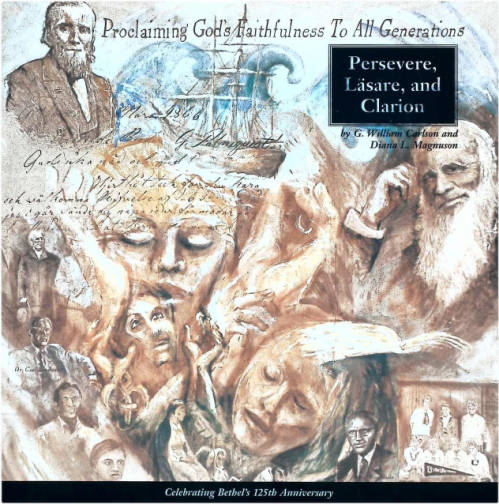

There had been a chapter on education in the Baptist General Conference in the Centenary History of that denomination (1952) by Adolf Olson, who had previously collaborated with his son Virgil on a brief 75th anniversary history of Bethel Seminary alone (1946). But it wasn’t until 1997 that Bethel College and Seminary got anything like a full accounting of its institutional history. For the institution’s 125th anniversary celebration, history professors G.W. Carlson and Diana Magnuson collaborated on a historical exhibit that became an impressive booklet, Persevere, Läsare, Clarion.

Like Adolf Olson, Carlson and Magnuson started their story back in Sweden, with the “readers” (läsare) whose Bible studies both contributed to a pietistic revival and violated that country’s law against conventicles unsupervised by Lutheran clergy. The consequences were especially harsh for revivalists who became Baptists, many of whom sought religious freedom in the United States — and soon developed educational institutions to train their clergy and laity. Also like Olson, the more recent Bethel historians understood milestones like centennials and quasquicentennials as providing occasions “to understand God’s work” (Persevere, p. 2). “Great is the Lord and most worthy of praise,” read the psalm on the booklet’s dedication page. “One generation will commend Your works to another” (Ps 145: 3, 4).

But unlike their predecessor, Carlson and Magnuson held terminal degrees in their field (both completed PhDs at the University of Minnesota) and were more cautious about attempting “providential” readings of Bethel’s past. While they clearly shared many of the religious beliefs and aspirations of their subject and took seriously how “Swedish Baptist pietist themes [impacted] the life and activity of Bethel amidst a changing clientele and educational environment” (9), theirs was historical scholarship that non-believers could recognize and appreciate. Even more carefully researched than A Centenary History, Persevere also did better at rooting Bethel’s experience in a larger social, cultural, and economic context. Its authors tracked a recurring tension between the preservation of ethnic and religious heritage and the irresistible pressures of “Americanization” and even offered judicious hints of critical evaluation.

Also unlike Adolf Olson’s pioneering work, the histories written by Carlson and Magnuson paid significant attention to the experience of women at Bethel. A former Bethel History and Political Science major herself (1988) who also served as the archivist of her university and denomination, Magnuson brought to the project particular expertise in women’s history, the subject of a course she taught often during her twenty-seven years on the faculty (1994-2021).

To a greater extent than either Olson, she and Carlson included women among the people accorded biographical — if not quite hagiographical — treatment. Among other illustrated supplements to the larger narrative, Minnie Hanson (Burma) and Olivia Johnson (the Philippines) appear early to illustrate “Bethel’s interest in missions” (22). Then Carlson and Magnuson profiled Esther Sabel, the long-serving Bible professor (1924-1958), and Effie Nelson, who taught German and other subjects during her 41-year career and also served as dean of women (1937-1962).

While those biographical inserts exemplified what feminist historian Gerda Lerner had called a “compensatory history” focused on the achievement of “women worthies,” Carlson and Magnuson also engaged in something more like Lerner’s next historiographical stage: a “contribution history” that would go beyond “great women” to describe more broadly “women’s contribution to, their status in, and their oppression by male-defined society.”

Hints of that kind of history show up early on, as when Carlson and Magnuson note that the newly built Academy building (dedicated 1916) had modern facilities like hot showers — “with separate entrances for boys and girls” — and that its co-curriculum included a girls-only speaking club, the Athenaean Society. But the most groundbreaking section of Persevere, Läsare, Clarion in this sense is the one dedicated to “multicultural and gender equity” efforts in the latter decades of the twentieth century, when Bethel — like many other American colleges and universities — grappled with the challenges posed by the Civil Rights Movement and second-wave feminism. Not only do Carlson and Magnuson feature a poem on racism by African American student Linda Frederickson ’91, but they allocate two pages to women’s athletics, which both offered “one illustration of the pursuit of gender equity on campus” and incurred “opposition from those who believed it was unfeminine and those who thought it was not economically viable” (46-47).

That opposition to the expansion of women’s sports is one of Persevere‘s occasional hints at how something like Lerner’s “oppression by male-defined society” had indeed inhibited and frustrated Bethel women.

Most notably, Carlson and Magnuson take time to document how Seminary dean Carl Gustaf Lagergren (1889-1922) “personally struggled with the issue of women in ministry.” (I’ve previously noted that women, after enrolling in small numbers under John Alexis Edgren, disappeared from the Seminary’s rolls until the very end of Lagergren’s tenure.) Not only did he blame problems in the Swedish church on “unbiblical preaching by women” (23), but Lagergren spoke out against the creation of the Bible and Missionary Training School, which offered two years of training to missionaries and Christian education workers, ministry roles open to women in Protestant denominations that otherwise largely limited their pulpits to men. “Nothing should give the suggestion that we were having a matrimonial bureau instead of a mission school,” Lagergren thundered. “Under any circumstances the feminine influence would be a hindrance to our brethren in their studies and work” (33).

Carlson and Magnuson note that Bethel president G. Arvid Hagstrom waited until Lagergren’s retirement to launch the BMTS, then hired Esther Sabel as its leader two years later. When Sabel retired in 1958, Effie Nelson wrote her a farewell letter: “I will miss you more than any other one faculty member will miss you because we have fought together for women’s rights on the campus for the greatest number of years” (quoted on p. 35).

In any event, the debate over women in ministry revived in the last thirty years of the century, though Carlson and Magnuson only hint at this in their 125th anniversary history. Invited to add a chapter about Bethel to an updated history of the modern BGC, Five Decades of Growth and Change (2010), they expanded on two incidents previously confined to a Persevere footnote. First, a debate over women in ministry pitted professors against each other in the pages of the student newspaper and denominational magazine; complementarians John Piper and Wayne Grudem and egalitarians Alvera and Berkeley Mickelsen went on to play key roles in the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood and Christians for Biblical Equality, respectively. Second, complementarian delegates to the BGC’s 1995 annual meeting tried and failed to block the faculty appointment of Carla Dahl, hired to lead the Seminary’s new program on marriage and family counseling.

Dahl won the vote to become the third woman in the history of the Seminary faculty, after Esther Sabel and Christian education professor Jeannette Bakke (hired 1978), and Jeannine Brown was hired to teach New Testament in 2000. “Although there are differing positions on the issue of women in ministry at Bethel Seminary,” Carlson and Magnuson concluded, “there is a general consensus that women should be part of the faculty and the student body, and that individual churches should make their own decisions about ordination” (Five Decades, p. 49).

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.