As when he wrote about the larger denomination in his Centenary History of the Baptist General Conference, women mostly stay in the background of Adolf Olson’s coverage of Bethel, the BGC’s college and seminary.

We hear the story of John Alexis Edgren and his theological school in ch. 11 of Olson’s Centenary History, but learn little of his wife, Anna (or Annie) Abbot Chapman, save that it was her frail health that caused Edgren to return to the United States a year before founding his small seminary in Chicago (p. 158). In a later chapter on “Educational Expansion,” Olson credits a “godly mother” with bringing about the conversion of Carl Gustaf Lagergren (484), but doesn’t probe the long-serving dean’s evident uneasiness about women studying at his seminary. Later, he alludes to a “lady member of the [Bethel Academy] class” of 1910 who spent a quarter-century as a missionary in Assam, India (p. 491), but doesn’t name her.

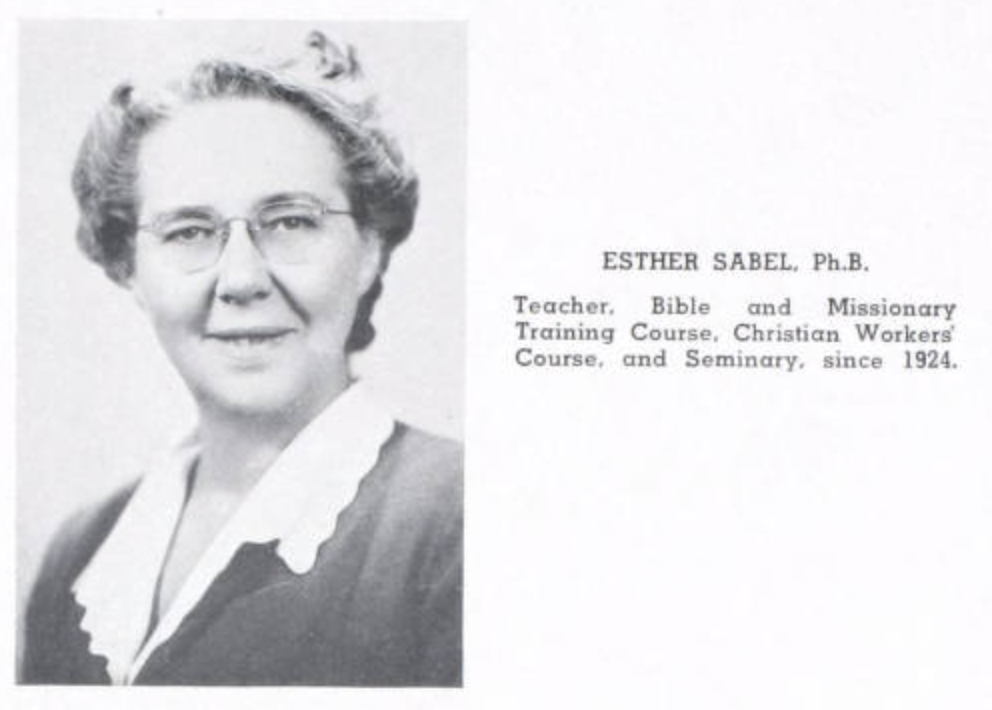

A few women’s names do show up, but with little explanation. Olson notes without comment that Edgren’s daughter Julia taught history and music when the Swedish Baptist Seminary temporarily relocated to St. Paul in 1884-85 (Centenary History, 166) and mentions in passing two pioneering faculty members from the school’s later time in that city: Esther Sabel and Effie Nelson.

Here we can fill in some of the story using the 75th anniversary history of Bethel Seminary that Olson wrote six years earlier with his son, Virgil. Without ever paying sustained attention to gender, that book does note that Elizabeth Johnson became the seminary’s first female student in 1879 — at least two years ahead of other Baptist seminaries — with three more women enrolling in the 1880s. While the Olsons don’t explain why women disappeared from the roster from 1887 to 1921 (largely the era of Lagergren), their exhaustive list of students through 1946 names more than fifty women — including “Mrs. Adolf Olson” (who took classes off and on for three years in the 1920s).

No Bethel woman is featured in any of the brief hagiographies (“saints’ stories”) that serve as a key storytelling device for Adolf Olson’s Centenary History. But Seventy-Five Years does include a brief biography of Esther Sabel. An honors graduate of the University of Chicago, Sabel studied briefly at Moody Bible Institute and Newton (MA) Theological Institution before coming to western Minnesota in 1922 to serve as English teacher and principal of the high school in tiny Parkers Prairie. In 1924, Bethel hired her to teach in its new Bible and Missionary Training School (BMTS), a two-year course (later halved in length) that “served a very distinct purpose in educating young men and women for more effective service on the home and foreign field” as missionaries and Christian education workers (Seventy-Five Years, 56). The Olsons praised Sabel, who taught at Bethel until her retirement in 1958, as”a very efficient and loyal member of the Bethel faculty” (57).

Updating the seminary’s history for its 110th anniversary, Bethel archivist Norris Magnuson noted that the founding of the BMTS significantly increased the seminary’s female student population, but he didn’t give Sabel the biographical treatment he accorded Bethel’s presidents and seminary deans — all men. The only woman to warrant her own section in Magnuson’s Missionsskolan was C. G. Lagergren’s wife, Selma, whom he credited with extending “the kind of congenial, family-like atmosphere that characterized the Seminary” in its earliest days, when Anna Edgren both served as the first librarian and “was said to have been nurse and mother to a host of seminarians” (47).

Selma Lagergren had lost her position as a schoolteacher in Sweden when she became a Baptist, then met her husband at a school in Sundsvall set up by the sectarian movement. Magnuson observes that she brought to the seminary during its second stint in Chicago the same “qualities of personality and Christian commitment that helped make Selma a winsome person and a gifted teacher….” One alumnus remembered her as “always like a mother and friend to the students,” but Magnuson described Mrs. Lagergren as doing more than standing in loco parentis to young immigrant men who were doubly far from home. She connected her husband to the Swedish temperance movement and supported Swedish Baptist missions both foreign and domestic. From 1906 until her death in 1911, Selma Lagergren made the seminary’s Chicago campus the home of the Morgan Park Mission Society, which “had as its two-fold purpose the assistance of needy seminarians and of retired Swedish Baptists who resided in the near-by and recently begun Fridhem home for the aged” (Missionsskolan, 47).

In incorporating the isolated stories of pioneering female leaders while paying little attention to the larger experience of Bethel women, Magnuson and the Olsons illustrated one common early approach to the writing of women’s history: what Gerda Lerner called “compensatory history.”

An immigrant from Austria, Lerner founded the first graduate program in woman’s history in the U.S. at Sarah Lawrence College in New York. In 1975 the new journal Feminist Studies invited her to summarize the historiography of women. That article (“Placing Women in History“) grew into the 1979 book pictured to the right.

“The first level at which historians, trained in traditional history, approach women’s history,” Lerner began her original article, “is by writing the history of ‘women worthies’ or ‘compensatory history.’ Who are the women missing from history? Who are the women of achievement and what did they achieve?” Lerner had taken this approach herself, teaching a “Great Women” course while she was still an undergraduate herself, and found it “perfectly understandable that after centuries of neglect of the role of women in history, compensatory questions” would be asked.

Nevertheless, she found this focus inadequate and potentially misleading:

The resulting history of “notable women” does not tell us much about those activities in which most women engaged, nor does it tell us about the significance of women’s activities to society as a whole. The history of notable women is the history of exceptional, even deviant women, and does not describe the experience and history of the mass of women.

A “great women” history, in that sense, is no better than one focused on “great men.” It focuses attention on a handful of exceptional individuals in ways that can blind us to the experiences of a larger — and largely marginalized — group.

So while I’m convinced that there is some value in Christian historians practicing a more measured version of hagiography — we should be inspired by pioneering women leaders like those we interviewed this summer — I think we need to look for other models that get at the broader experience of women at Bethel. In the last post in this series, we’ll see if more recent histories of Bethel engaged in something more like the “contribution history” that Lerner described as the next stage of historiography: “describing women’s contribution to, their status in, and their oppression by male-defined society.”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.