One advantage of presenting my research in the form of a digital history rather than a more traditional publication is that it’s easy to incorporate both still and moving images — not just to add breaks to the text, but to help illustrate, enrich, humanize, and sometimes complicate the narrative. So I’m looking forward to spending more time looking through digitized and archival collections of Bethel photographs.

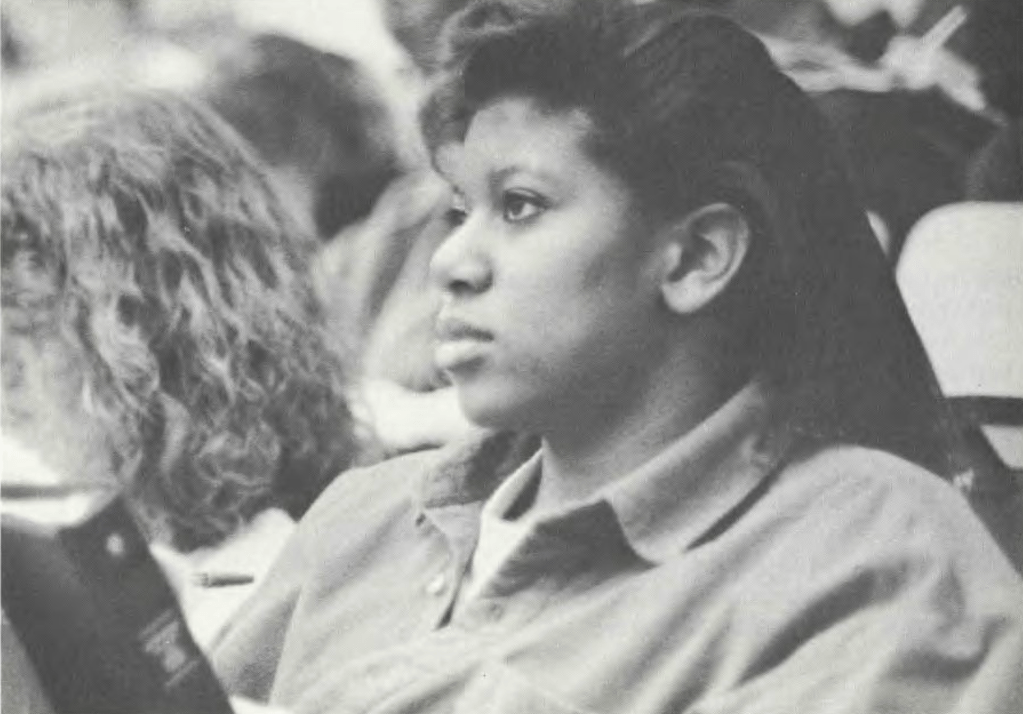

I’ve only dipped into that kind of evidence so far, perusing some of the yearbooks available in our digital library. And then only because I needed to identify an image that I could use as a kind of emblem for this project — at least, for its early days as a research blog. I don’t know that I’ll stick with it once the full project is ready to go next year, but I think the photograph I found is a good first choice for at least three reasons.

First, it comes from the 1972-73 yearbook, which provides a visual reminder that I’m focusing on the period in Bethel history that began that year, when the College joined the Seminary on the Lake Valentine campus in Arden Hills.

Second, I wanted to underscore that there’s no such thing as a single story of what it’s like to be a woman at Bethel, by visualizing at least one kind of diversity within that population. There weren’t many students of color on campus at that point in Bethel’s history, but 1972-1973 happened to be the senior year for Peninah Apela, who finished her English major in less than three years and was returning to her husband and four children in Nairobi, Kenya. Earlier in the same yearbook, her roommate contributed a touching tribute:

What can I say about someone I lived with for one and a half years? That she liked to listen to Jim Reeves and Kris Kristofferson? That she made delicious chicken and rice casseroles spiced with curry? That she came speaking English and left with a lot of American slang?

…I could mention that those years were crammed with alot [sic] of work and new experiences yet no day passed that she didn’t long to be home with her family. What can I say about Peninah but that she is my friend?!

Peninah’s roommate, the woman standing on the left of the photo, was a Social Sciences major from Isle, Minnesota named Connie Larson. Her campus job became her career: she worked as a librarian at Bethel for about thirty years, dying far too young in 2006. So third, including her image hints at a theme that arose again and again in our oral history project this summer: some women who came to Bethel as students made it their professional home.

Like any kind of historical evidence, photographic sources must be approached carefully and critically. “They seem utterly real,” warned columnist Walter Lippmann, since photographs “come, we imagine, directly to us, without human meddling….” But it’s not that simple. It’s not always clear who produced those images, for what which reason, or for which audience. The identification of who’s depicted isn’t always available or accurate, and sometimes a photographer or editor has framed or cropped the image in significant ways. And we can debate what photographs, like any source, actually mean.

Still, photographs can be especially significant in answering historical questions on which other evidence is silent. Social historians have used them to reconstruct the lives of people who didn’t have the ability to produce and preserve documents. That’s not the case here, but in theory, I could use yearbook images of fashion and friendship, relationships and routines to help analyze shifting ideas of gender roles and gender identity.

But I’m also trying to bear in mind that photographs — like everything else in the historical record — testify through their absence, not just their presence.

While interviewing a faculty colleague this summer, she was mostly quite positive about her experience as a woman at Bethel. But she did recall a moment, early in her career, when the new academic catalog came out. As usual, it included numerous photos, about thirty featuring faculty. But only one female professor was included, and then as part of a panel with several men.

Over lunch she and other colleagues debated what to make of that omission. One person suggested that the catalog editors were trying to emphasize racial diversity that year. “By putting a lot of students of color in the catalog,” replied a male professor, “Bethel was communicating this is what we want Bethel to be like. And we’re not choosing to do that, do it that way with women on the faculty.”

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.