Few historians ever break entirely new ground. We might bring new perspectives to new evidence or use new methods to answer new questions, but we are all revisiting — and sometimes revising — what others have already written about the past.

So before I get any farther into my own attempt at writing a history of Bethel University that centers its women, I thought I’d look back at how previous historians of Bethel and its denomination have — or haven’t — told the stories of its women. We’ll start with the seminary professor who started to modernize how Swedish American Baptists understood their past.

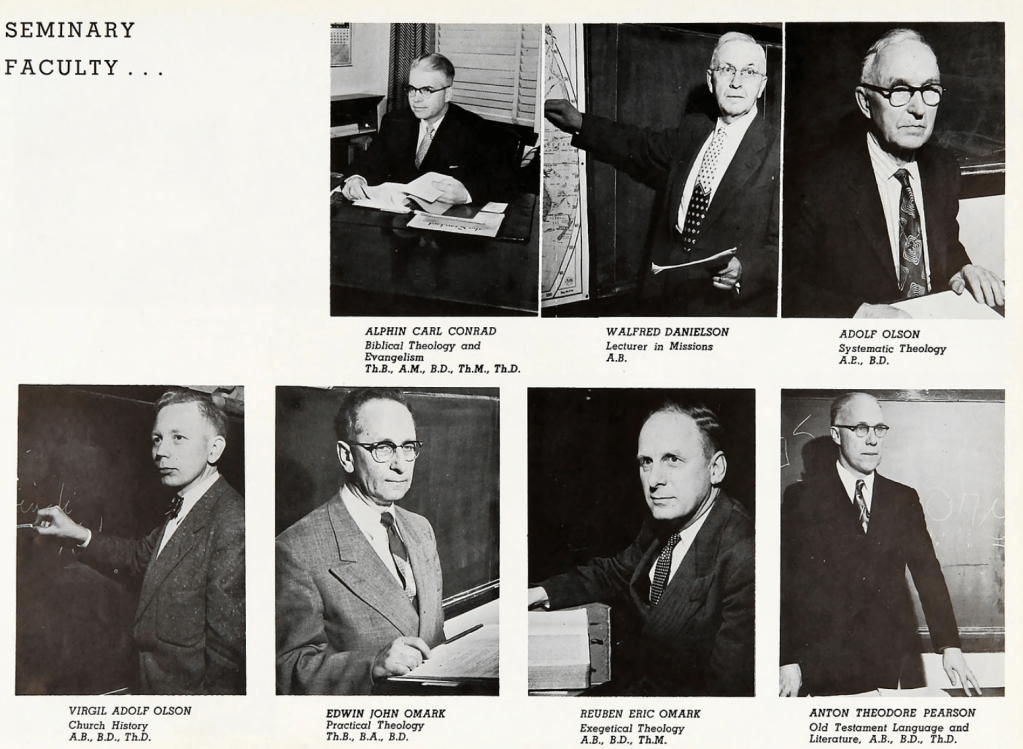

While there had been earlier attempts to tell the story of the Swedish Baptist movement, Adolf Olson (1886-1955) was the first trained historian to take on that project. After beginning his education in the Swedish Theological Seminary at the University of Chicago, just before that school moved to Minnesota and became Bethel Seminary, Olson continued his studies at Macalester College and the University of Minnesota. In 1915 he joined the faculty of Bethel Academy, then moved to the Seminary four years later, teaching church history and systematic theology into the 1950s, when his son Virgil succeeded him.

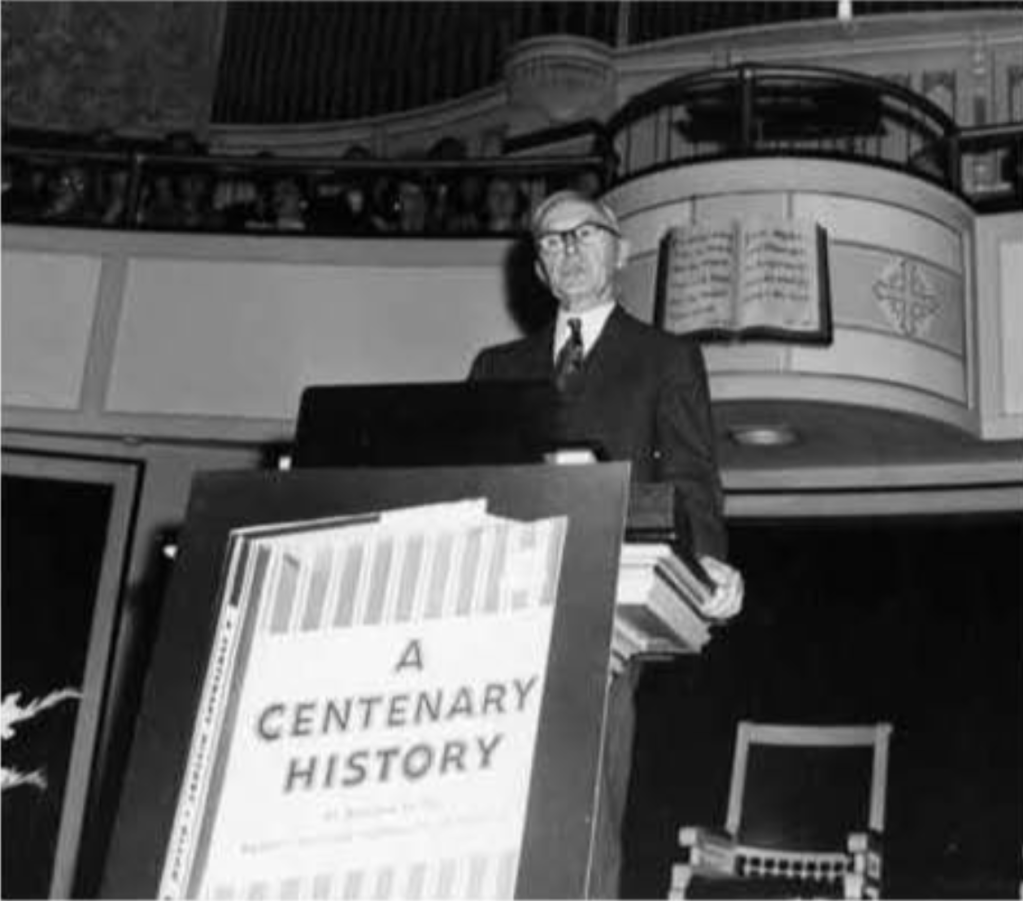

The Olsons had already collaborated on a 75th anniversary history of the Seminary in 1946. Virgil then helped his father complete his landmark achievement, a denominational history of the Baptist General Conference (BGC) published in time (1952) to mark the 100th anniversary of the first Swedish Baptist congregation in the United States. Virgil later recalled that “when father had completed the final paragraph, mother and I knelt with him by the dining room table and thanked God that the writing of the hundred year history of the Baptist General Conference was completed.”

Not surprisingly, then, A Centenary History is not a dispassionate exercise. Written by an author who was both historian and eyewitness to history, it’s imbued with Swedish Baptist piety and reflects the post-WWII confidence and optimism of an immigrant denomination that was stepping into the evangelical mainstream, starting new churches at home and an independent missionary project abroad. “In fact,” admits J. O. Backlund in his foreword, “there are instances when [the author] grows subjectively lyrical in his enthusiasm for the upbuilding of churches, the rebirth of souls, the genesis and growth of institutions. If objective aloofness is an absolute condition for relating important things that have come to pass in individuals, churches, and the denomination at large, he will probably be willing to admit that he has been at fault as his enthusiasm has made him feel like shouting forth an occasional hallelujah. No doubt he will say he could not do otherwise, for thus the spirit moved him.”

Though Olson insisted that his “aim had been that of the fair and unbiased historian,” he closed his preface “with a prayer to the great Head of the church that His name may be glorified in every line, and that [this history] may inspire us and our descendants to follow the Master and the pioneers by whose life and labor we have been enriched.”

So where did the “life and labor” of women fit into that story?

The only chapter of A Centenary History to pay focused attention to women is one of the two written by Virgil Olson. But it’s noteworthy how the younger Olson started his four-page overview of BGC women’s organizations:

The history of nearly every church is rich with incidents concerning the sacrificial labor, the missionary vision, and the practical service of the women… The place of the women in the church in the early part of the conference century was not one of prominence, but rather of work in the background. Without the work of the women in the church, however, many churches would have completely failed. (A Centenary History, p. 555)

Indeed, women mostly remain in the background of the older Olson’s writing, but they’re neither insignificant nor (always) anonymous.

At several points, Olson credits women with taking the impetus in starting early BGC churches. The first Swedish Baptist congregation in Denver, Colorado formed in 1886 because “God had touched the hearts of four women, who, like the devout women in Philippi, were wont to gather for prayer.” Concerned for the souls of their friends, they asked John Alexis Edgren to send one of his seminary students to pastor them (362). That seminary later merged with Bethel Academy, founded at Elim Church in northeast Minneapolis just over twenty years after “a few women who assembled to pray and to sew” first formed a “mission circle” in that neighborhood with Anna Sandberg, a home missionary sent out by Minneapolis’ First Swedish Baptist Church (185). Those women’s names are lost to history, but whenever possible, Olson goes out of his way to identify pioneering women, like the five who made up the majority of the nine members who chartered Houston (MN) Baptist in 1853.

One of them (Inga Christina Berndtson) may have been unmarried, but Olson takes for granted that most BGC women would primarily serve the church in the domestic sphere. Though he describes fathers as playing the lead role in the devotional life of Swedish Baptist immigrant families, Olson notes that mothers stepped in when “the father was still unsaved,” telling the story of one alcoholic father being saved after finding “his wife and children on their knees in prayer for his conversion” (75). Later, Margreta Bodien — whose husband, Olof, pastored First-Minneapolis from 1893 until his death in 1915 — stands in for dozens of unnamed saints when Olson describes her as “an ideal minister’s wife,” who made the Bodien house “known far and wide for its genuine hospitality” and used it “as a temporary home for many immigrant young women” (255).

(The Bodien name was later attached to a women’s dorm on the Snelling Avenue campus of Bethel College. Bodien Hall lives on as a residence on Freshman Hill of the Arden Hills campus.)

But at several points in A Centenary History, Olson hints at the BGC offering women a wider range of more autonomous opportunities for ministry. About the same time that Elim Baptist started Bethel Academy, members of the congregation on Payne Avenue in St. Paul launched the Mounds Park Sanitarium, whose nursing school “provided excellent training to more than one thousand young women not only in the profession of healing but also, which is even more important, in a wholesome spiritual and Christian atmosphere.” Moreover, many of the first nurses trained by what became Mounds-Midway School of Nursing followed the lead of their superintendent, Mary Danielson, by “serving Christ in the foreign missions fields” (575).

Danielson had lived in Japan in the early 20th century, not long after Gerda Paulson first arrived in that country in 1899. Indeed, women accounted for ten of the first sixteen BGC foreign missionaries, sent out under the auspices of the American Baptist Missionary Union in the late 1800s. That early missions advance began with Johanna Anderson, a Swedish immigrant who had originally taught school in central Minnesota. “A saintly mother had dedicated Johanna to the foreign missionary task,” recounts Olson, in one of his more “subjectively lyrical” passages, “and the young lady was not disobedient to the heavenly vision calling her to tell the story of Jesus in lands beyond the seas” (517), first leaving for Burma in 1888 and dying in that country in 1904.

(Click here to read Anderson’s 1892 report in The Baptist Missionary Magazine.)

“From their very beginning Swedish Baptists have been a missionary-minded people,” wrote Olson, and women also served in that capacity much closer to home than Burma, Japan, or the Philippines. For example, more than half of the nine home missionaries first sent out by First Swedish Baptist of St. Paul in the late 1880s were women (194), and we’ve already noted the role of Anna Sandberg in founding a church on the other side of the Mississippi River.

Most strikingly, Olson credits a Swedish evangelist named Amanda Yman with helping bring revival to multiple Baptist communities in the Upper Midwest. In 1888 Yman first came to Stanchfield Township in Isanti County, Minnesota, where “preaching by women was then a brand new thing among Swedish Baptists; hotly disputed by some, and by reason of that made more attractive to others. She returned the following year, and again in 1893. Large crowds came to see this woman evangelist and to hear her proclaim Christ” (110).

Later in 1888, Yman also led revivals on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. “Crowds of people gathered” that winter at the Swedish Baptist church in Iron Mountain,

and a deep revival of religion developed. Meetings were often prolonged until midnight. Nobody seemed to be in a hurry to go home. That woman was very courageous. It was said that she was not afraid of Satan himself. (A Centenary History, p. 297)

Likewise, “large crowds flocked to hear the attractive lady preacher” in Duluth, Minnesota in 1890, “and many repented and believed in the Lord” (217).

While Adolf Olson didn’t center the experiences or perspectives of BGC women, nor attend to the social, cultural, and other factors keeping them in the background of their movement, he didn’t ignore their contributions. And when women do step into the foreground of A Centenary History, they can seem to foreshadow the more prominent roles that future women would play within an expanded sphere of influence in their denomination and (more commonly) its university.

One goal of this blog is to help involve members of the Bethel community in doing the history of Bethel, so comments are always welcome! Just know that if you leave a comment at the project blog, I’ll take that as expressing your permission to quote it in the project.